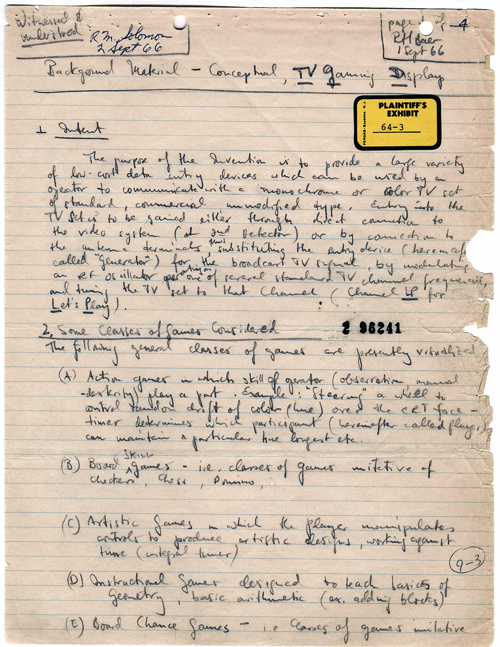

The first page of Baer's 1966 concept document for a "TV Gaming Display." Ralph H. Baer Papers, AC0854, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian.

Fifty years ago, in September 1966, an unassuming engineer heading a research group at the defense contractor Sanders Associates in New Hampshire hand-penned a remarkable four-page document. “The purpose of the invention,” he wrote on September 1, 1966 while waiting for a colleague at the New York City bus terminal, “is to provide a large variety of low-cost data entry devices which can be used by an operator to communicate with a monochrome or color TV set.”[1] What Ralph Baer did next would transform interactive entertainment and give rise to an industry that earned nearly $102 billion in revenue worldwide in 2015.[2]

Outlining how to make television responsive and envisioning a world of video games, Baer’s hardware-based model for video games opened the door to a market that soon acted as a driving force for increased computer processing speeds, data storage, and other aspects of the information age we often take for granted. While several brands of personal computers were introduced in 1977 as devices to catalog recipes and balance checkbooks, people actually bought them for gaming, just as new iterations of cell phone technology today enable more complex games, faster internet access, and easier viewing of videos, not better phone calls.

Baer, a refugee from Nazi Germany, had been taught using discrete electronics (before integrated circuits) and graduated with a B.S. in television engineering in 1948. His initial description was written as an engineer’s plan for “a new way of interfacing with a TV set,” as Baer himself put it years later.[3] He nonetheless also outlined seven “classes” of games, including action games, sports games, artistic games, instructional games, board games, card games, and games of chance. In addition to the games themselves, Baer developed techniques to control the horizontal and vertical images displayed on the screen, along with synchronized sounds, and created various controllers and other peripherals that were connected to the TV to play the games he created.

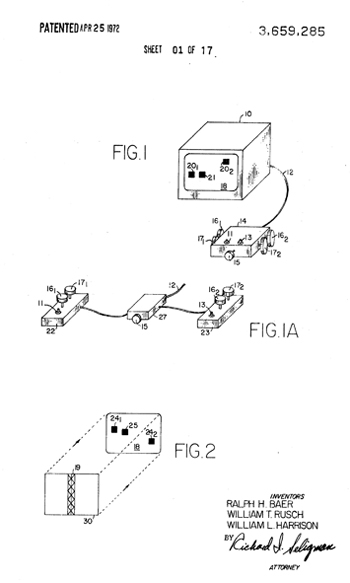

Baer’s plans for a game controller to move an image on a TV screen as described in his US Patent 3,659,285.

Autumn 1966 was a remarkable historical moment in which to create the concept for video games. The space race and cold war between the United States and Russia were intensifying. A week after Baer drafted his memo, Star Trek premiered on NBC, showcasing not just quirky planets and advanced computers, but also ways for humans of diverse races and ethnicities to collaborate in problem solving. Unlike in fictionalized space, the United States still had segregated schools, despite passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964. Activists continued to push for greater access to education and opportunities for minorities to work and live where they chose. A new generation of youth born after World War II was beginning to cohere with protests against the Vietnam conflict and multi-day music, art, and poetry events such as the “Trips Festival” taking place in San Francisco.

As Baer developed the first home video game system, the U.S. economy was growing at an annual rate of 9.5 percent (in nominal terms), with unemployment below 4 percent. Manufacturing had rebounded strongly from a recession in 1960-1961 and employed 17.9 million Americans (28 percent of working adults) compared to 12.3 million today (less than 9 percent of employed adults). But there were early signals that changes were coming. Western Europe was rebuilding, with lower labor costs and newer factories. Populations in Asia were booming. And international negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade would eventually expose US manufacturers to more competition. Prescient futurists like Peter Drucker were predicting a shift to “knowledge work” for the United States, with requirements for different forms of education and new opportunities for entertainment industries.[4] Overall, it was a fertile point in history for envisioning new worlds, interactivity, and gaming.

Within days of writing his initial concept document, Baer had sketched a schematic of circuits to place two spots on a TV screen that could be moved by a controller. From there he recruited several employees to work on building and testing prototypes. A series of patent filings followed, first describing “apparatus and method for recording a coded pattern on a CRT display” in 1968, then “apparatus and methods … for the purpose of playing games, training simulation, and for engaging in other activities by one or more participants” 18 months later.[5]

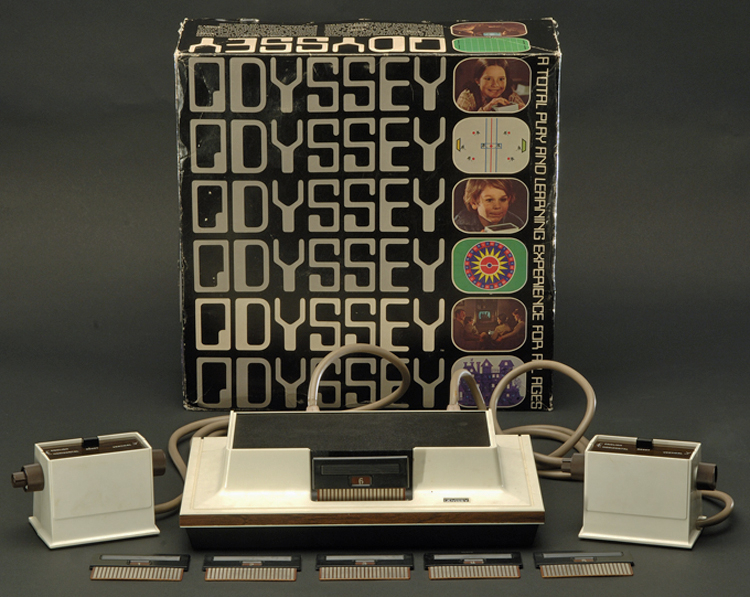

In 1972, their work was available to consumers as the Magnavox Odyssey, giving families the opportunity to play “electronic games” on their home televisions.[6] Other inventors had created games on an oscilloscope at Brookhaven National Lab and on mainframe computers at MIT and Stanford, but Baer’s video games were different. Not restricted to elite institutions and high-performance computers, they were intended for everyone.

The Magnavox Odyssey Video Game Unit, 1972. Division of Medicine and Science, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian.

From there, some aspects of video game innovation accelerated, while others moved at a slower pace. A Rolling Stone article from 1972 reported on elite programmers at Stanford playing the minicomputer game “Spacewar!” (then a decade old) even while suggesting, “Ready or not, computers are coming to the people.”[7] The Atari 2600 brought gaming to a wide population starting in 1977, followed by a notorious video game industry bust in 1983. The industry revived by the late 1980s and has been booming in recent years. One growth metric stands out across video game history: the Odyssey game set invented by Baer and his team had 28 games (each with one level) by mid-1973. “No Man’s Sky,” a game launched in August 2016 (a screenshot is at the top of this page), offers 18 quintillion (1.8 x 1019) discrete planets with unique ecosystems for players to explore. The average compounded rate of increase for video game complexity works out to 15,950 percent annually, some 26 times that of the overall U.S. economy!

The Lemelson Center is partnering with video game experts and a group of museums and archives across the United States to create the “Videogame Pioneers Archive" to record in-depth oral history interviews with the first generation of video game inventors and preserve documents, game consoles, game code, and other materials for the future.

[1] Ralph Baer, Videogames in the Beginning (Springfield, NJ: Rolenta Press, 2005), 25.

[2] Source: https://www.statista.com/topics/868/video-games/

[3] Ralph Baer, Oral History conducted by David Allison, John Fleckner, Joyce Bedi, and Arthur Molella, April 22 and 23, 2003, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, side 2.

[4] Peter F. Drucker, Landmarks of Tomorrow (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1959).

[5] Baer, Ralph H. Recording CRT light gun and method. US Patent 3,599,221, filed March 18, 1968, issued August 10, 1971; Baer, Ralph H., William T. Rusch, and William L. Harrison. Television gaming apparatus and method. US Patent 3,659,285, filed August 21, 1969, issued April 25, 1972.

[6] The Odyssey game set was marketed as an “electronic game simulator.” See Magnavox Service Manual 6500 (February 1974).

[7] Stewart Brand, “Spacewar,” Rolling Stone (December 7, 1972), 50-58.