Introduction

Did you know that Alexander Graham Bell was born in Scotland? He is only one example of a foreign-born inventor who sought opportunity in the United States.

The contributions of immigrant inventors to the American economy and society as a whole are well-documented. In 2017, Harvard Business School scholars found that “technology areas where immigrant inventors were prevalent between 1880 and 1940 experienced more patenting and citations between 1940 and 2000.” Researchers at Stanford University published findings in 2018 showing that “immigrants account for 16% of all US inventors from 1976 through 2012.” They also noted that “immigrants account for about 23% of total innovation.”

An Aspen Institute report in 2019 affirmed these scholars’ findings, stating that immigration “drives innovation. It offers businesses access to a larger, more diverse marketplace of human capital and talent, as well as to new ways of thinking and differing approaches to solving common problems. Innovation requires a risk-taking ecosystem, and many immigrants are by their very nature willing to take risks to change and improve their lives, having relocated to a foreign land often with no native language skills.”

The stories here—drawn from the collections of the National Museum of American History—attest to the creativity and determination represented by diverse immigrant inventors over more than a century.

Throughout 2021, you can see many of the objects illustrated here in the Inventive Minds gallery in the Lemelson Hall of Invention, first floor, west wing, National Museum of American History.

ARGENTINA | Manoel de la Peña

Little is known about the life of inventor Manoel de la Peña. His 1870 patent for a typesetting machine states that he was living in New York City, but was a citizen of Argentina.

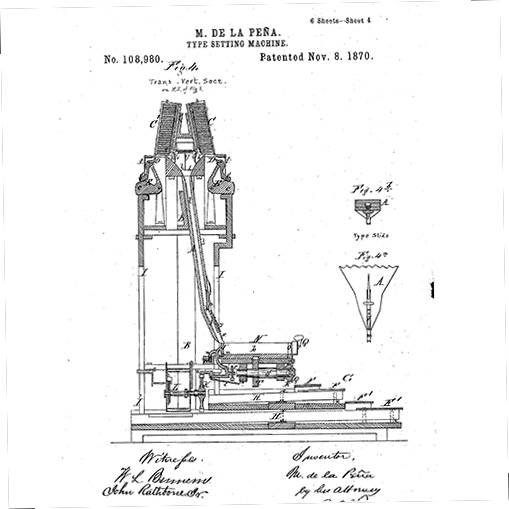

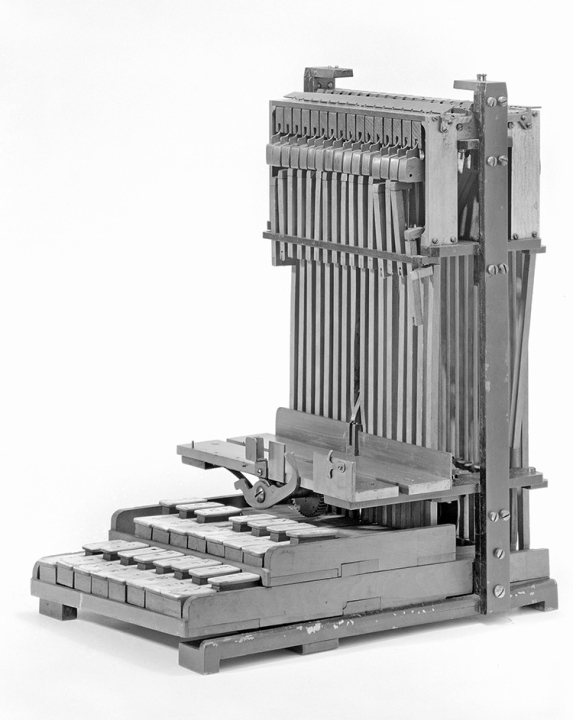

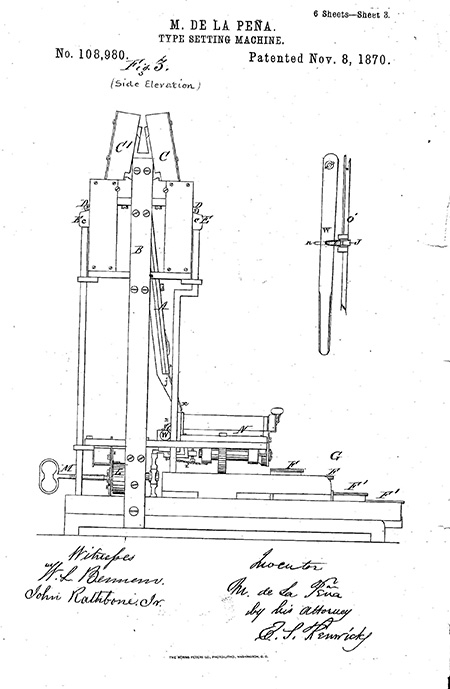

The model shown here was submitted with his patent application. The invention allowed a typesetter to press one of the keys to release a piece of metal type. Gravity pulled the piece through the vertical slides on the machine to form a line of characters that could later be inked and printed with a printing press.

Patent model that accompanied Manoel de la Peña’s patent application for a “Type Setting Machine.” US Patent 108,980 was issued to de la Peña in 1870, National Museum of American History, GA.89797.108980. © Smithsonian Institution; photo MAH-67905

US Patent 108,980 for a “Type Setting Machine” was issued to Manoel de la Peña in 1870. Courtesy of USPTO

Learn more about Manoel de la Peña’s life and work:

- Explore the National Museum of American History’s graphic arts patent models

BELGIUM | Leo Baekeland

Leo Baekeland (1863–1944) was born in Belgium. He studied chemistry at the University of Ghent and earned his PhD before coming to the United States in 1889.

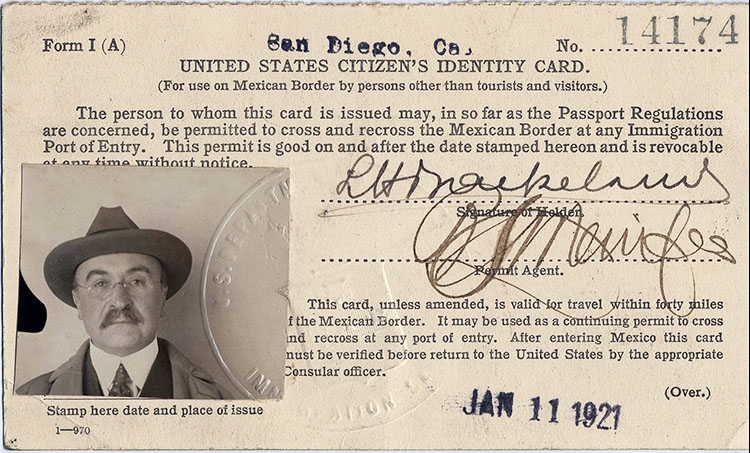

Leo Baekeland’s United States citizen identity card, 1921, AC0005-0000052-1. Leo H. Baekeland Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

His first successful invention was a new type of photographic paper called Velox that could be developed under artificial light. He sold the rights to Kodak and used the money to fund his own laboratory.

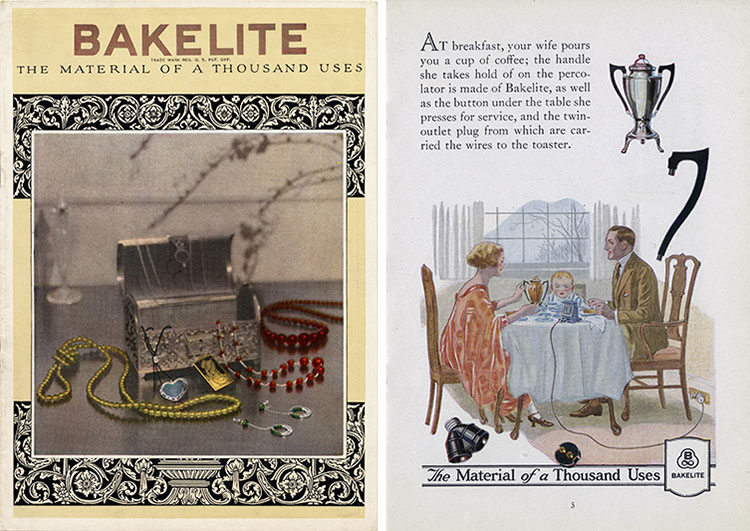

In 1907, Baekeland’s experiments with phenol and formaldehyde yielded the first fully synthetic plastic, which he named Bakelite. Easy to mold, incredibly strong, and extremely versatile, Bakelite was dubbed “The Material of a Thousand Uses,” with applications ranging from electrical insulators to telephones to jewelry.

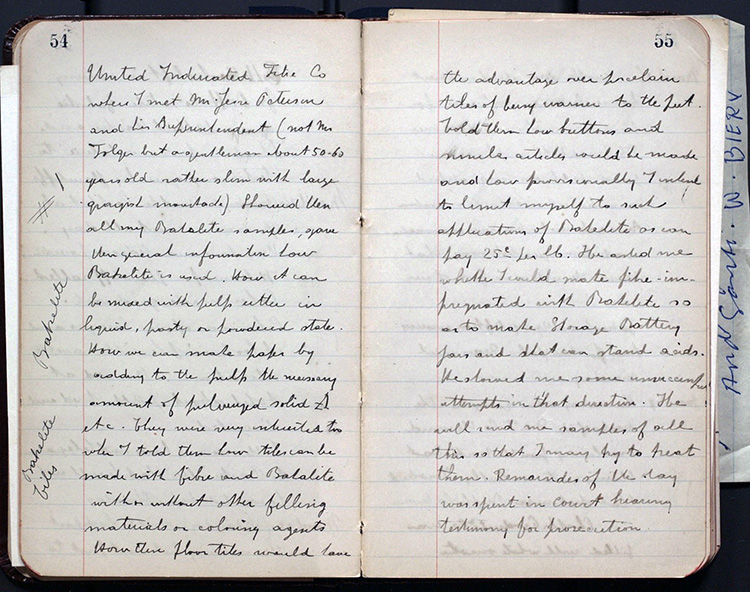

Leo Baekeland first used the term “Bakelite” in this entry in his Diary No. 2, 1908, AC0005-D02-0030. Leo H. Baekeland Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

“Bakelizer” reaction vessel, about 1909, National Museum of American History, 1983.0524.01. © Smithsonian Institution

The steam pressure vessel pictured here was used by Leo Baekeland around 1909 to produce commercial quantities of Bakelite, by reacting phenol and formaldehyde under pressure at high temperatures.

The "Bakelizer," part of the National Museum of American History's collections, is still in operating condition. It is about 35 inches wide, 40 inches deep, and nearly 72 inches tall.

Leo Baekeland (second from left) in Hamburg, Germany, about 1910, AC0005-0000001. Leo H. Baekeland Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Cover and interior page from the catalog, “Bakelite: Material of a Thousand Uses,” 1924, AC0008-0000009. J. Harry DuBois Collection on the History of Plastics, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Bakelite billiard balls, in their original wooden box, made by the Hyatt-Burroughs Billiard Ball Co. of Newark, NJ, after 1910, 1981.0976.01. © Smithsonian Institution; photo by Richard Strauss, RWS2016-09957

Leo Baekeland at the Berlin Zoo, 1932, AC0005-0000119. Leo H. Baekeland Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Learn more about Leo Baekeland’s life and work:

- Read Beyond Bakelite: Leo Baekeland and the Business of Science and Invention by Joris Mercelis (MIT Press, 2020)

- Explore the Leo H. Baekeland Papers at the Archives Center, National Museum of American History

FRANCE | Michael Bouchet

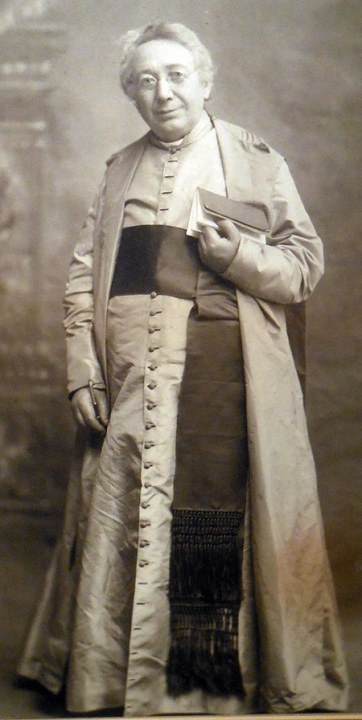

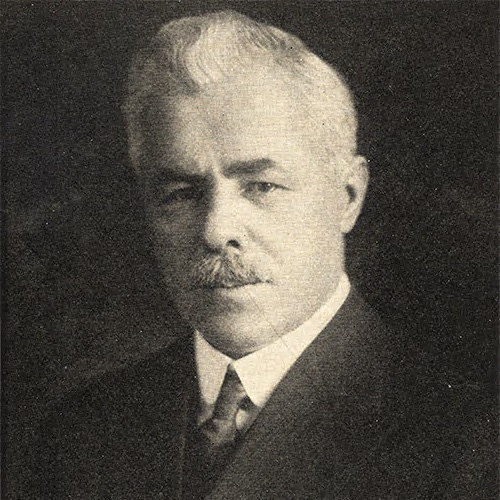

Monsignor Michael Bouchet, undated. Courtesy of Vatican Observatory

Michael Bouchet (1827–1903) was a Catholic priest who was born in France and immigrated to the United States in 1853. He not only had a respected ecclesiastical career, becoming a monsignor in 1899, but also a mechanical avocation. Called an “incessant thinker” by a contemporary, Bouchet’s inventive mind resulted in devising automatic snakes to frighten his acolytes, and a folding bed and fire escape for his own use.

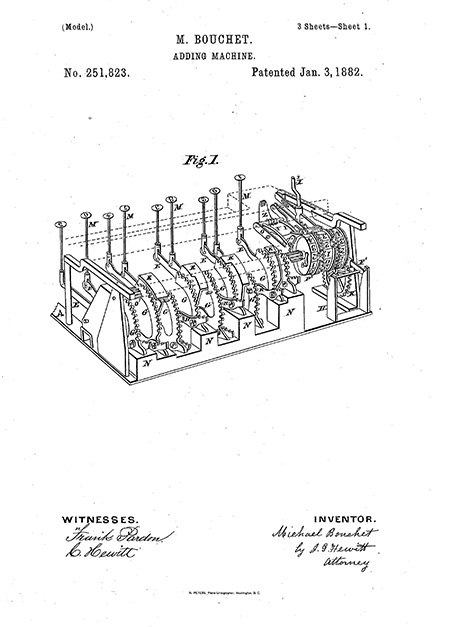

Beginning in the 1860s, Bouchet invented adding machines to assist in keeping his diocese’s accounts. He only patented the later versions of the adding machine, including the one shown here, patented in 1885. It could add single columns of numbers and, as the patent states, the instrument was designed to be “cheap, durable, reliable, and not liable to get out of order.”

Bouchet adding machine, around 1885, National Museum of American History, MA.323630. Gift of Victor Comptometer Corporation. © Smithsonian Institution; photo SIA-2006-500

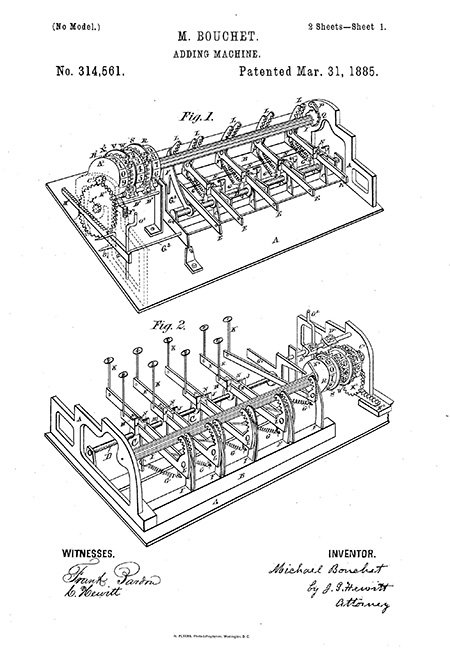

US Patent 314,561, “Adding Machine,” issued to Michael Bouchet, 1885. Courtesy of USPTO

According to National Museum of American History curator Peggy Kidwell, “this machine was used to add single columns of digits. Depressing a key depressed a lever and raised a curved bar with teeth on the inside of it. The teeth on the bar engaged a toothed pinion at the back of the machine, rotating it forward in proportion to the digit entered.

“A wheel at the left end of the roller turned forward, recording the entry. A pawl and spring then disengaged the curved bar, preventing the roller and recording bar from turning back again once the key was released.

“Two additional wheels to the left of the first one were used in carrying to the tens and hundreds places, so that the machine could record totals up to 99. Left of the wheels was a lever-driven tack and pinion zeroing mechanism.”

US Patent 251,823, “Adding Machine,” issued to Michael Bouchet, 1882. Courtesy of USPTO

Learn more about Michael Bouchet’s life and work:

- Explore the National Museum of American History’s collection of adding machines

GERMANY | Ralph Baer

GERMANY | Charles (Karl) Nessler

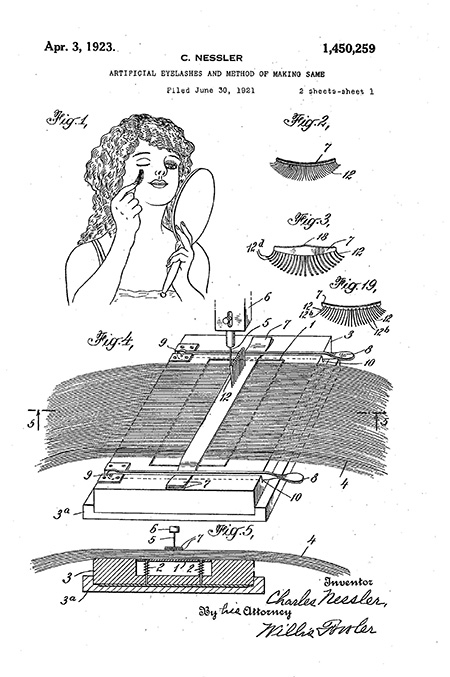

Charles Nessler’s US Patent 1,450,259 for artificial eyelashes, 1923. Courtesy of USPTO

Charles (Karl) Nessler (1872–1951) was born in Germany and built the successful hair care business C. Nestle Co. in London. He had invented artificial eyelashes and eyebrows before he demonstrated his breakthrough machine in 1905 for permanently waving hair.

Instead of curling straight hair with heated irons (a process that only lasted until the hair was washed), Nessler’s invention heated sections of hair that had been soaked in a chemical solution and wrapped around rods. The wave produced withstood washing.

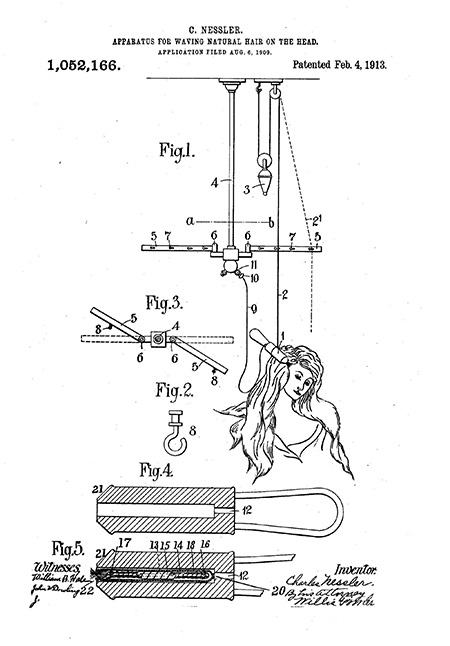

Charles Nessler’s US Patent 1,052,166 for a hair waving machine, 1913, is one of several that Nessler received for such devices. Courtesy of USPTO

During World War I, Britain seized the assets of citizens of enemy countries and Nessler fled to the United States in 1915. He re-created his success, leading to a merger that launched the Nestle-LeMur Co. in 1928.

The machine shown here represents one of the patents assigned to Nestle-LeMur and is a variation on Nessler’s original apparatus.

Nestle-LeMur Multi-Triumph Duo Control hair waving machine, late 1920s. Gift of Irving Kopf. © Smithsonian Institution; photo by Jaclyn Nash, JN2020-00118

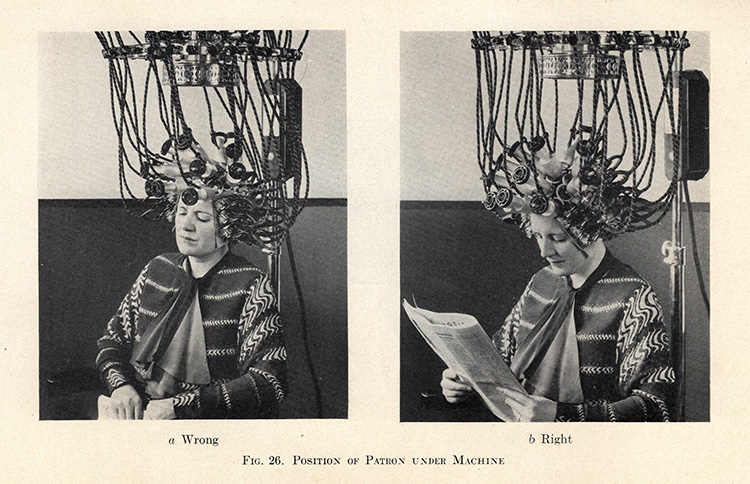

“Position of Patron under Machine,” from Basic Science of Hair Treatments, Nestle-Lemur Co., 1935.

Learn more about Charles Nessler’s life and work:

- Read Life magazine’s tribute to Nessler, “A Revolutionist Dies,” in the 5 February 1951 issue (starting on page 37), available from Google Books

- Visit the virtual exhibition, Karl Ludwig Nessler: Erfinder der Dauerwelle (in German)

- Read about the history of the permanent wave machine, from the Wisconsin Historical Society

GERMANY | Charlotte Cramer Sachs

Charlotte Cramer Sachs self portrait, around 1953, AC0878-0000008. Charlotte Cramer Sachs Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Charlotte Cramer Sachs (1907–2004) was born in Germany and came to the United States in 1924. Her creative talents extended to art, languages, music—and invention.

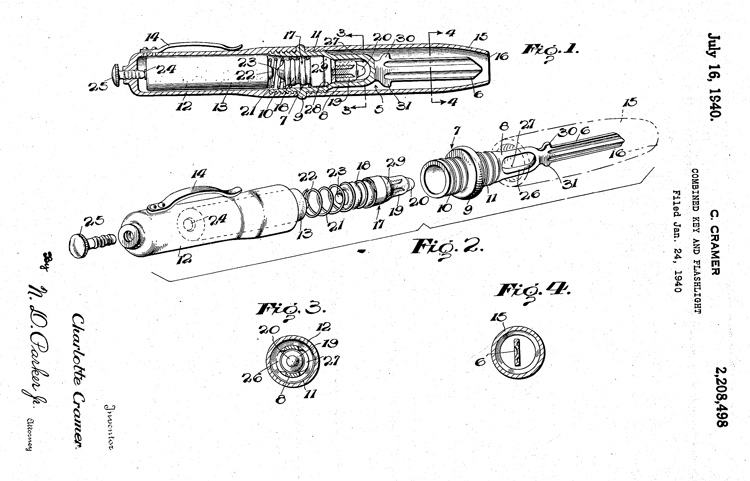

She received her first patent (US Patent 2,208,498) in 1940 for a combination key and flashlight.

Charlotte Cramer Sachs received US Patent 2,208,498 in 1940 for a combination key and flashlight. Courtesy of USPTO

As a single working mother during World War II, Sachs experienced firsthand the demands on the growing number of women who worked outside the home.

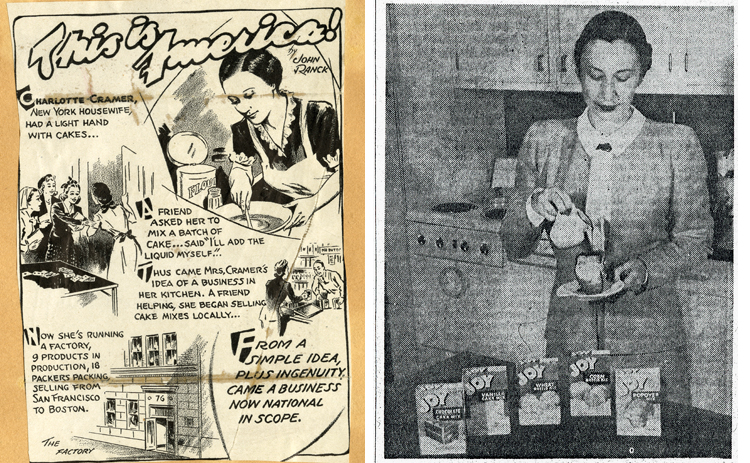

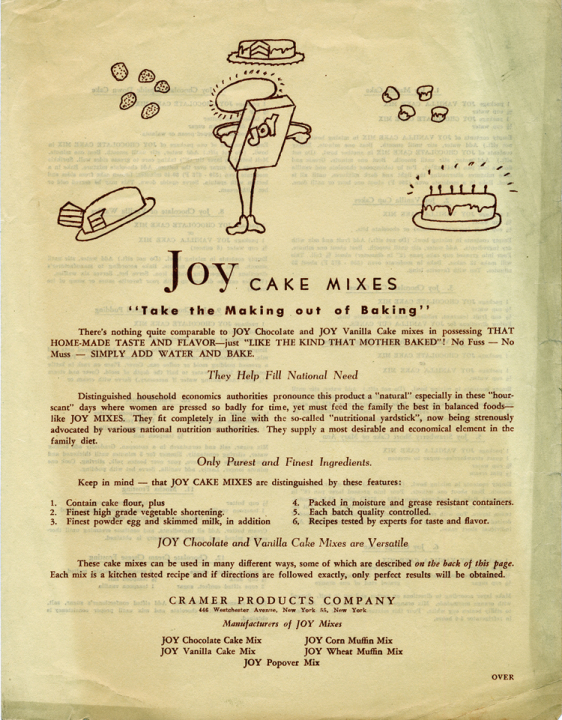

Her line of instant cake and muffin mixes helped save time and ease the effects of wartime food shortages.

Charlotte Cramer Sachs in the press: (left) illustration from This is America, Industrial Press Service, October 16, 1944, AC0878-0000070, and the news article, “Only Water Is Needed for Ready-Mix Popovers,” New York Herald Tribune, around 1947, AC0878-0000010. Charlotte Cramer Sachs Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

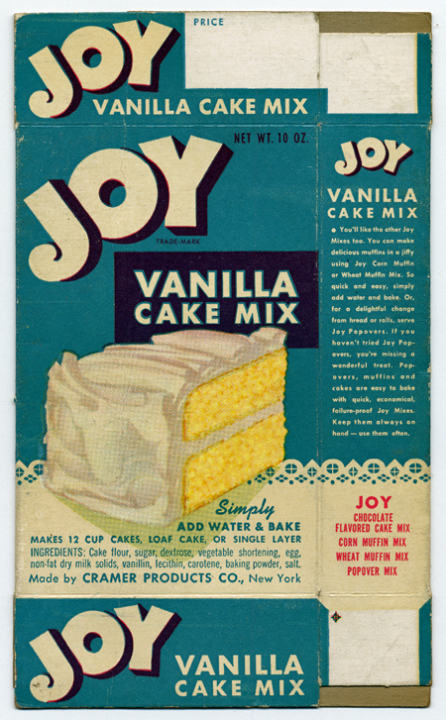

She revealed her delight in inventing in the name of her company—Joy Products.

Product box, Joy vanilla cake mix, 1947, AC0878-0000026-01. Charlotte Cramer Sachs Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Informational sheet, “Joy Cake Mixes—‘Take the Making out of Baking,’” undated, AC0878-0000012-01. Charlotte Cramer Sachs Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Charlotte Cramer Sachs kept inventing throughout her long life.

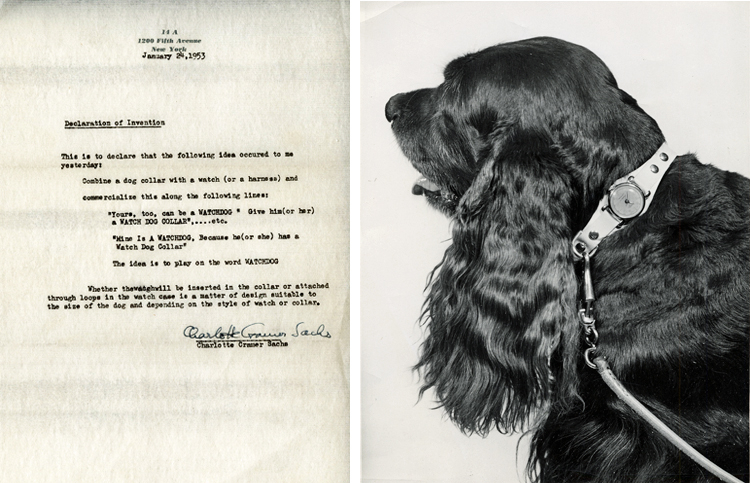

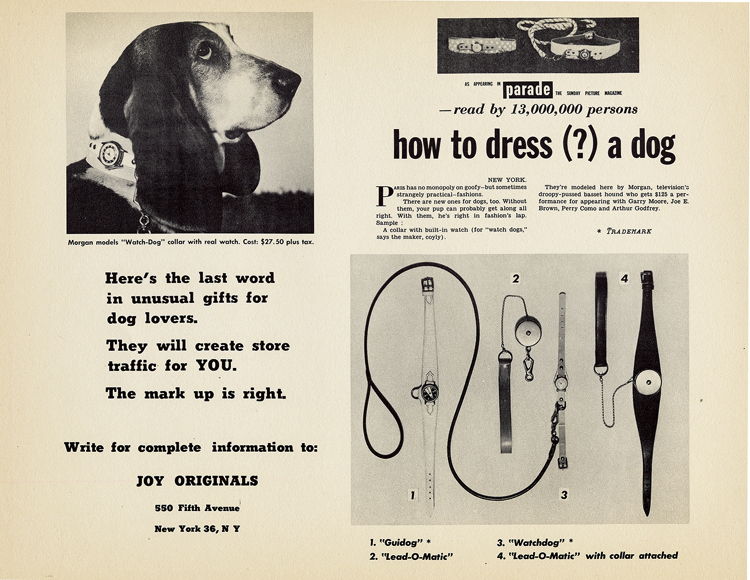

She designed several pet accessories in the early 1950s, including the “Watch-Dog,” a dog collar with a watch on it.

Charlotte Cramer Sachs designed a dog collar with an attached watch, turning anyone’s pup into a “watch-dog,” AC0878-0000039 (left) and AC0878-0000006. Charlotte Cramer Sachs Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Advertisement for the Watch-Dog” collar, AC0878-0000007. Charlotte Cramer Sachs Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

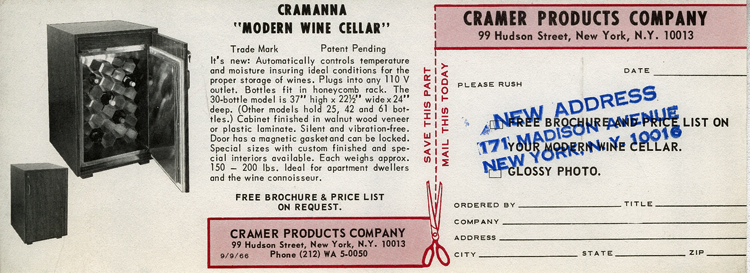

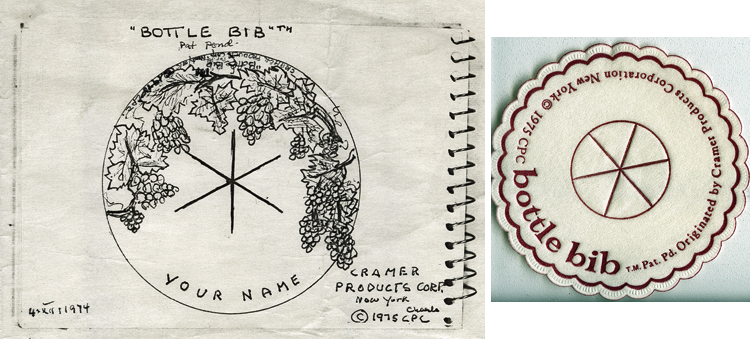

And for wine lovers, she invented the “Modern Wine Cellar” for storing wines at the proper temperature and humidity, and the “Bottle Bib,” to prevent drips.

Charlotte Cramer Sach’s “Modern Wine Cellar” stored wines at the proper temperature and humidity. With different size models designed to store between 25 and 61 bottles, the cabinet was, according to the ad, “ideal for apartment dwellers and the wine connoisseur,” AC0878-0000049. Charlotte Cramer Sachs Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Charlotte Cramer Sachs’s sketch (left) for the “Bottle Bib” that stopped drips, AC0878-0000052, and the finished commercial product, AC0878-0000051. Charlotte Cramer Sachs Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Learn more about Charlotte Cramer Sachs’s life and work:

- Explore the Charlotte Cramer Sachs Papers at the Archives Center, National Museum of American History

- Read an in-depth biography of Charlotte Cramer Sachs written by Lemelson Center archivist Alison Oswald

- Read Charlotte Cramer Sachs’s story written especially for kids

HUNGARY | Charles (Károlyi) Eisler

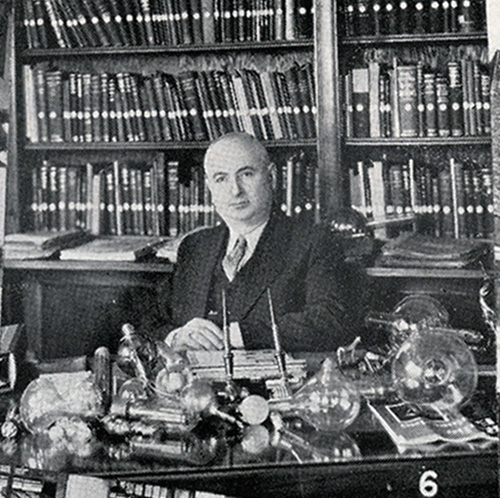

Hungarian-American inventor Charles (Karólyi) Eisler at age 50 in 1934, from his autobiography, The Million Dollar Bend (New York: William-Frederick Press, 1960), p. 235.

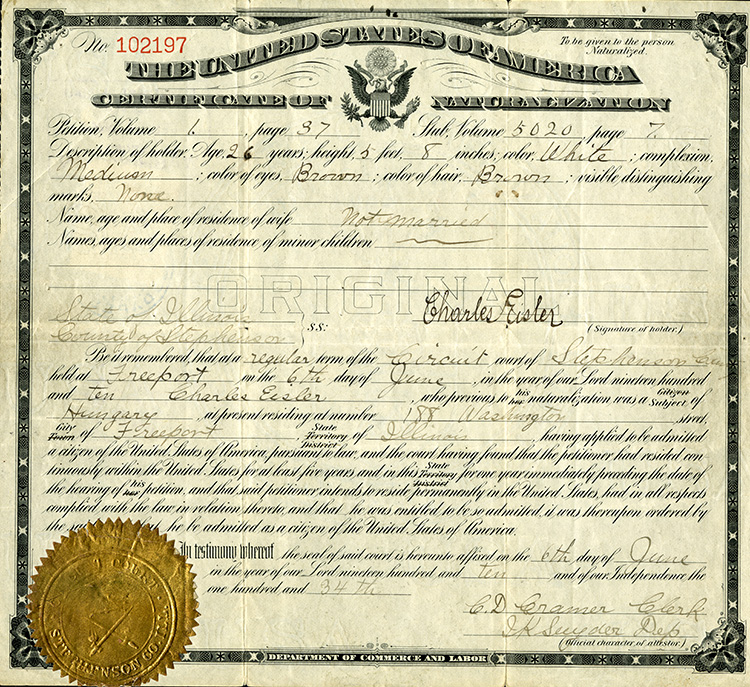

Charles (Károly) Eisler (1884–1973) was born in Hungary, studied and worked in Germany, and arrived in New York in 1904. He returned to Hungary in 1912, but came back to the United States in 1914.

Certificate of Naturalization issued to Károlyi (Charles) Eisler, 1910, AC0734-0000007-01. Eisler Engineering Company Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

When Westinghouse bought the small company that Eisler worked for, he lost his job—and gained an understanding of how the big electrical companies (General Electric, Westinghouse, and RCA) squeezed out smaller competitors. He started Eisler Engineering in Newark, New Jersey, in 1920, in part to buck that monopoly.

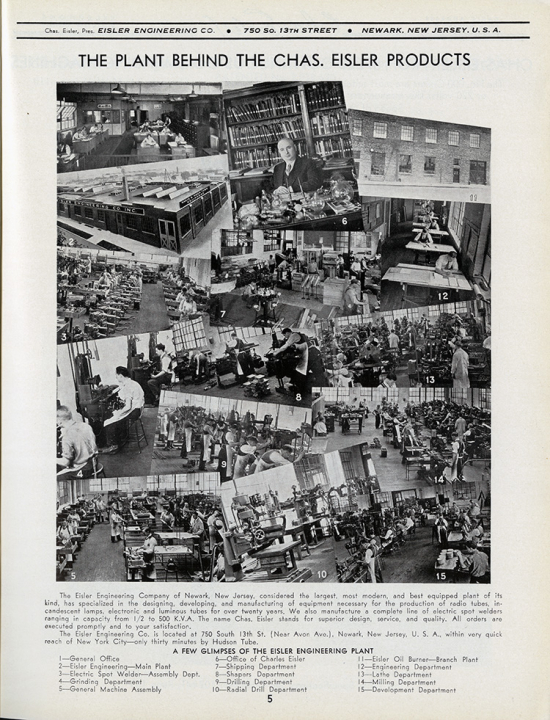

“The Plant Behind the Chas. Eisler Products,” Neon Sign Machinery catalog, Eisler Electric Corp., 1938, AC0734-0000050. Eisler Engineering Company Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

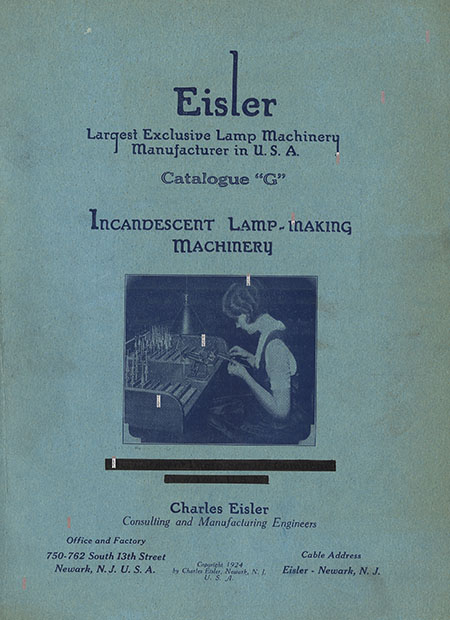

Eisler Engineering Co. Incandescent Lamp-Making Machinery catalog, 1924., AC0734-0000001. Eisler Engineering Company Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

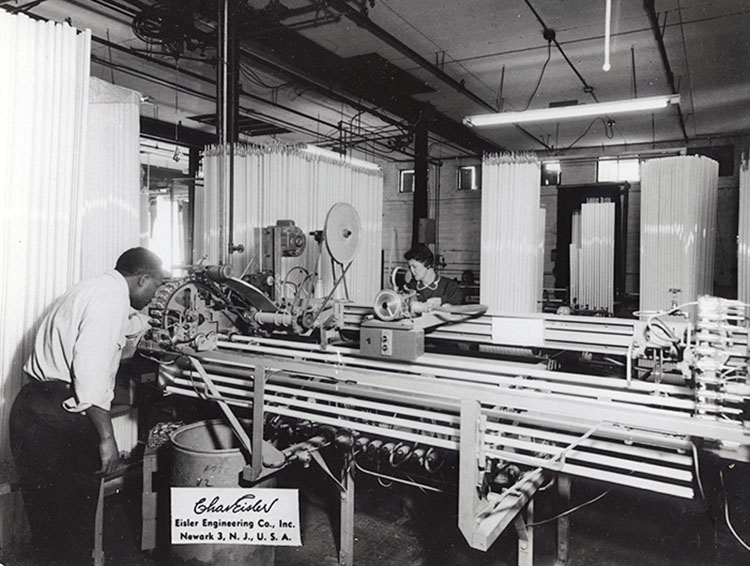

Eisler’s successful company manufactured equipment for producing all kinds of light bulbs, television and radio tubes, welding equipment, and laboratory apparatus.

The foreword to the 1924 incandescent lamp-making machinery catalog states, “Mr. Chas. Eisler, Chief of Staff, has designed, developed and constructed more Automatic Lamp Machinery than any other individual.”

Tube manufacture, undated, AC0734-0000035. Eisler Engineering Company Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

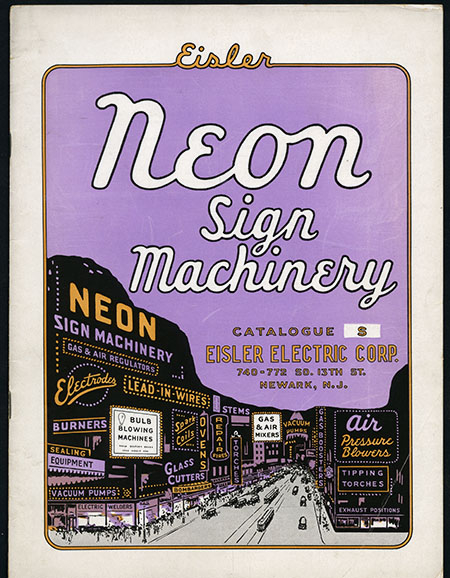

Eisler Electric Corp. Neon Sign Machinery catalog, 1933, AC0734-0000041-01. Eisler Engineering Company Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

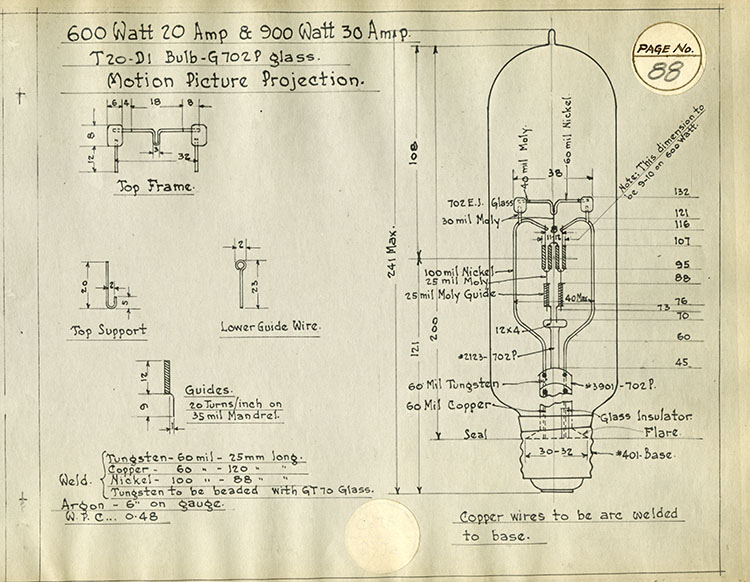

An Eisler Engineering Co. drawing for a movie projector lamp, AC0734-0000040. Eisler Engineering Company Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Eisler was active in the Newark, New Jersey, Hungarian community. He donated equipment, clothes, and money to a variety of organizations that assisted Hungarians in the United States and in Hungary.

A series of photographs marking the donation of two ambulances to the US Army by the Hungarian-American community of Newark, New Jersey on 25 July 1943. Left: Charles Eisler introducing Major General Herbert Hargreaves at the podium. Center: Women in traditional Hungarian costume on the steps of City Hall. Right: Eisler presenting the ambulance donation on behalf of Newark’s Hungarian-American community. From Charles Eisler, The Million Dollar Bend (New York: William-Frederick Press, 1960), p. 242.

Learn more about Charles Eisler's life and work:

- Explore the Eisler Engineering Company Records at the Archives Center, National Museum of American History

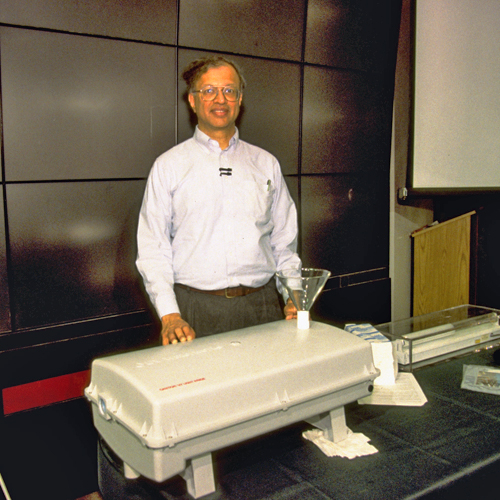

INDIA | Ashok Gadgil

IRELAND | David McConnell Smyth

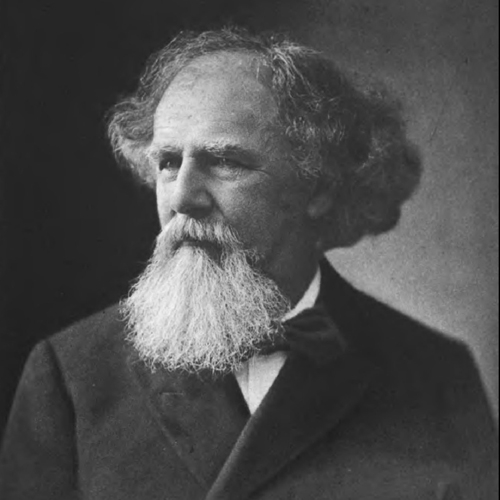

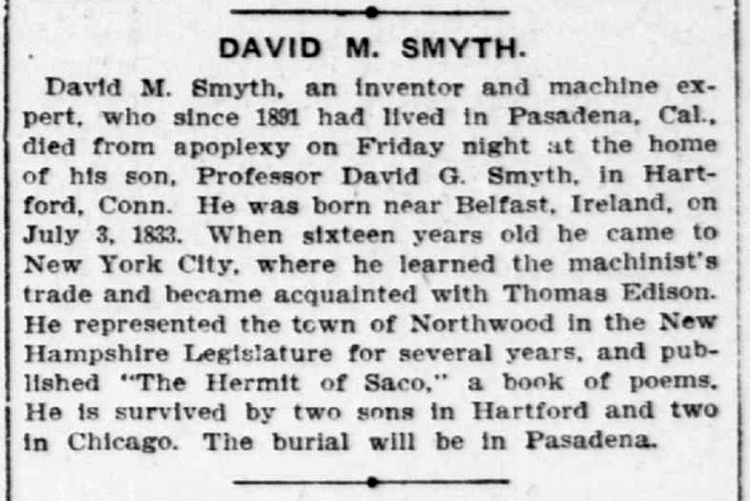

David McConnell Smyth (1833–1907) was born in what is now Northern Ireland; his family moved to the United States in 1835.

Smyth became a prolific inventor. National Museum of American History curator Joan Boudreau notes that Smyth was “granted patents for some forty inventions for clothing and book sewing, as well as mining and irrigation machines.”

David McConnell Smyth’s obituary, New-York Daily Tribune, 13 October 1907

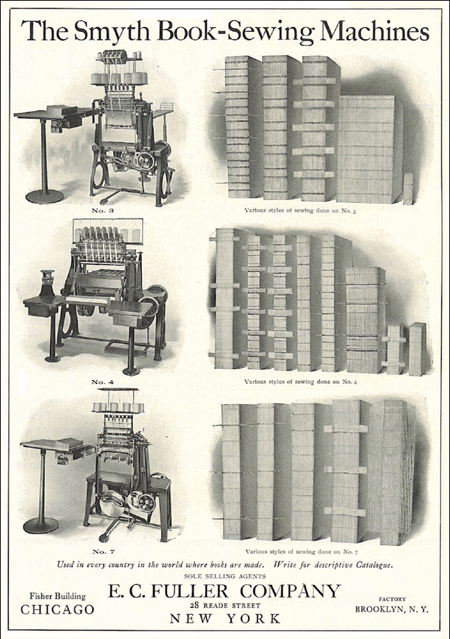

“Smyth Book-Sewing Machines,” sold by E. C. Fuller, New York, 1906. The ad notes that Smyth machines are used in every country in the world where books are made.” Courtesy of Fiddlebase

Smyth was especially known for his bookbinding equipment. His inventions were so influential that, as Boudreau points out, Smyth has been “memorialized with the term ‘Smyth sewn’ or ‘Smyth sewing,’ which refers to his inventions having to do with the ‘method of sewing together folded, gathered, and collated signatures with a single thread sewn through the folds of individual signatures.’ His many inventions inspired the formation in the 1880s of the Smyth Manufacturing Company in Hartford, Connecticut, which successfully produced examples of his machines for the market.”

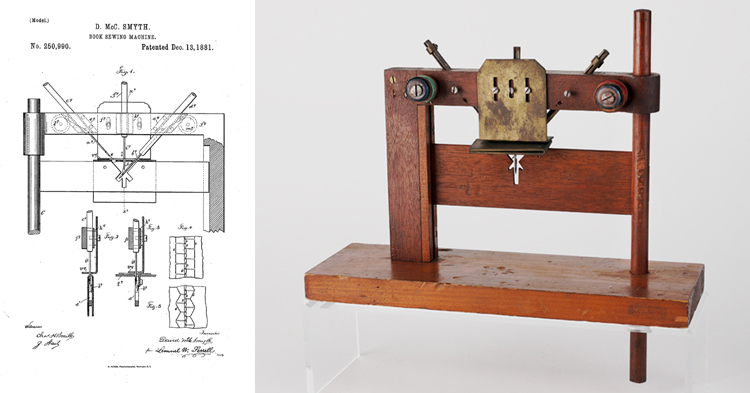

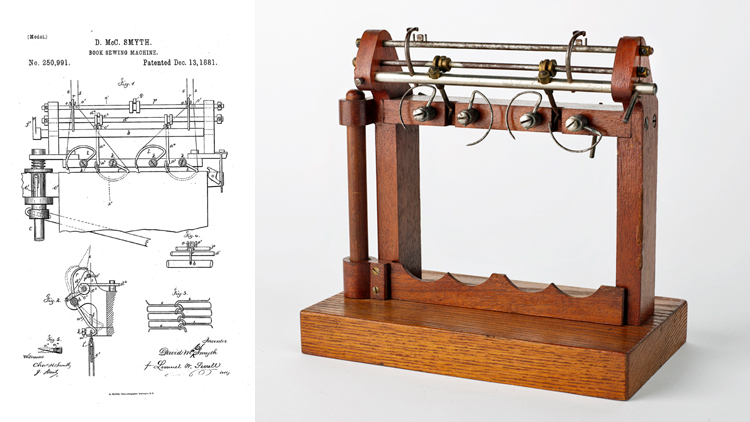

The models shown here, part of the National Museum of American History’s collections, were submitted with Smyth’s patent applications for machines that stitched together groups of pages of a book, called signatures, before a cover was attached.

Figures from David McConnell Smyth’s US Patent 250,990, issued in 1881, and the model that he submitted with his application, NMAH GA.89797.250990. Courtesy of USPTO and Smithsonian Institution; photo by Richard Strauss, RWS-2020-00481

Figures from David McConnell Smyth’s US Patent 250,991, issued in 1881, and the model that he submitted with his application, NMAH GA.89797.250991. Courtesy of USPTO and Smithsonian Institution; photo by Richard Strauss, RWS-2020-00481

Learn more about David McConnel Smyth’s life and work:

- Read curator Joan Boudreau’s blog about David McConnell Smyth

- Explore the National Museum of American History’s collection of graphic arts patent models

MEXICO | Victor Ochoa

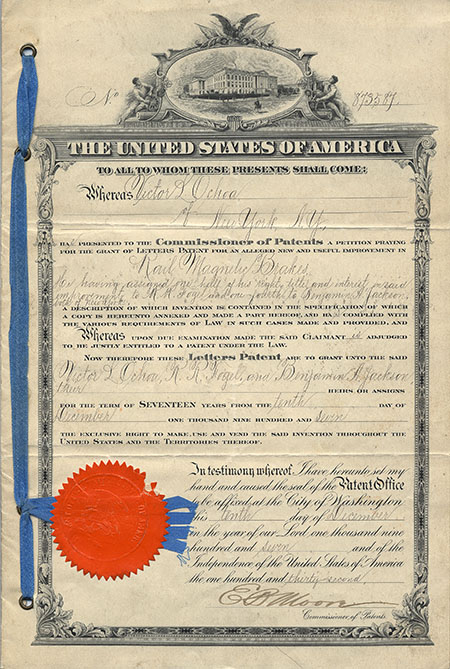

US Patent 873,587, issued to Victor Ochoa for a magnetic railway brake, 1907, AC0590-0000005. Victor L. Ochoa Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Victor Ochoa (1850–1945?) was born in Mexico and became a United States citizen in 1889. He was a revolutionary, a journalist, a miner, an aviator, a business owner, a prisoner at Leavenworth federal penitentiary, a friend of President Theodore Roosevelt, and for a while, a phantom (he faked his own death to avoid a $50,000 bounty on his head).

He was also an inventor, and his inventions were as diverse as the rest of his life story—an adjustable wrench, magnetic brakes, a wind-powered electrical generator, a fountain pen, a reversible motor, and the Ochoaplane, an airplane with folding wings.

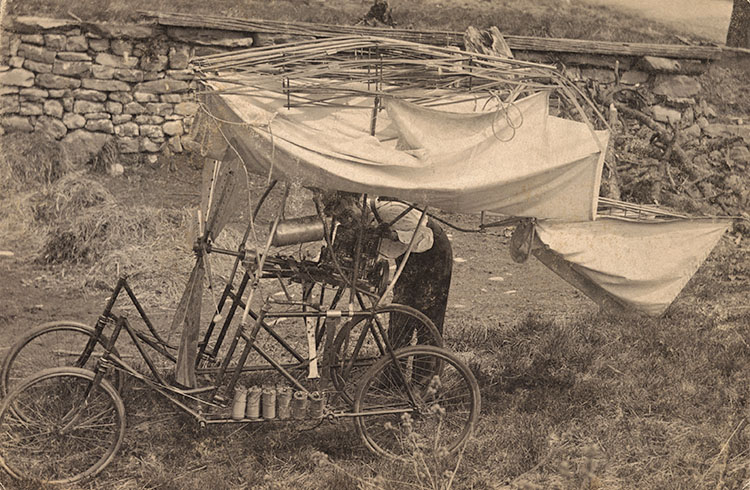

Victor Ochoa with his folding wing plane (wings folded), 1933, AC0590-0000006. Victor L. Ochoa Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

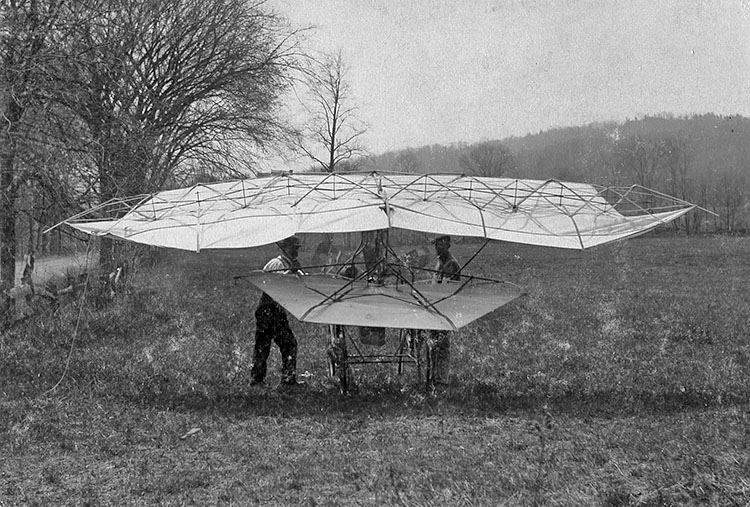

Victor Ochoa’s folding wing plane (wings unfolded), 1933, AC0590-0000002. Victor L. Ochoa Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Left: Victor Leaton Ochoa, inventor and Mexican revolutionary, undated, AC0590-0000008. Right: The “Ochoaplane” invented by Victor Ochoa around 1908-1911, undated, AC0590-0000009. Victor L. Ochoa Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

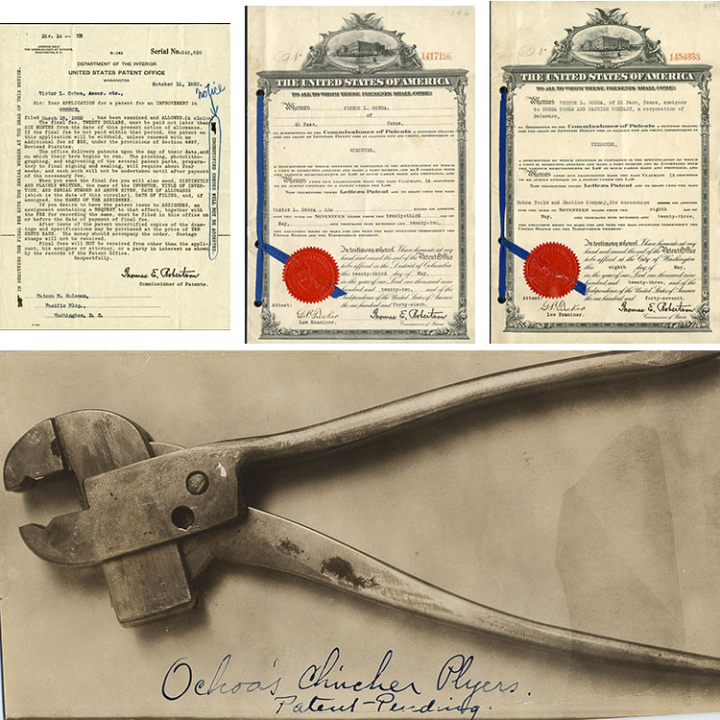

Victor Ochoa’s wrench inventions (clockwise from upper left: Victor Ochoa’s application for a patent for a wrench, AC0590-0000013; US Patent 1,417,196, AC0590-0000014; US Patent 1,454,333, AC0590-0000015; and Ochoa’s “clincher plyers,” AC0590-0000003. Victor L. Ochoa Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Learn more about Victor Ochoa’s life and work:

- Explore the Victor L. Ochoa Papers at the Archives Center, National Museum of American History

POLAND | Semi Joseph Begun

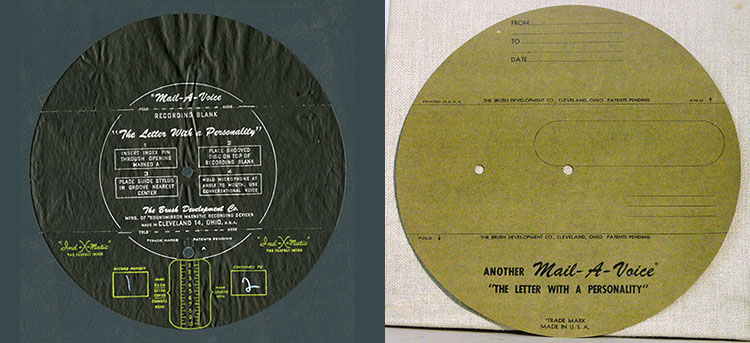

Brush Company “Mail-A-Voice” dictating machine, late 1940s, 1995.3101.01. © Smithsonian Institution, photo by Hugh Talman, 2000-2653-05-1

Semi Joseph Begun (1905–1995) was born in what is now Poland. He received his PhD in Germany in 1933, immigrated to the United States in 1935, and joined the Brush Development Co. in Cleveland in 1938.

Begun was a pioneer in magnetic sound recording, designing machines that recorded on wire during World War II.

In the late 1940s, he invented this office dictating machine called the “Mail-A-Voice.” Unlike reel-to-reel tape machines, the Mail-A-Voice recorded onto flat paper or plastic discs.

Front and back of a Mail-A-Voice disk, circa 1947-1950, AC0535-0000014 (left) and AHB2009q18664 (right). The disks were either paper or plastic, were coated with a magnetizable powder, and were flexible enough to be folded and mailed. Archives Center, NMAH, and National Museum of American History

The disks could be folded and mailed in an ordinary business envelope. Begun used the recorder to send audio letters to his mother.

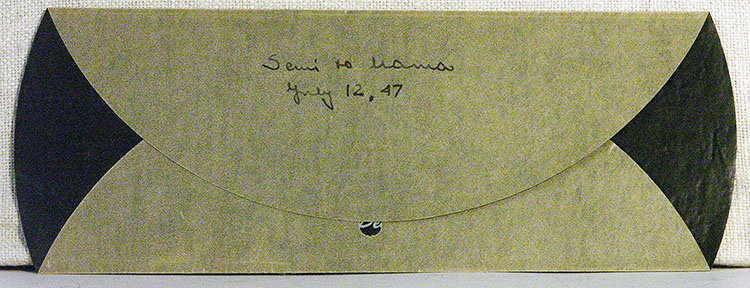

Semi J. Begun also used the Mail-A-Voice for personal correspondence. The museum has several disks that are audio letters from Begun to his mother. National Museum of American History, 1995.3101.05. © Smithsonian Institution; photo AHB2009q18672

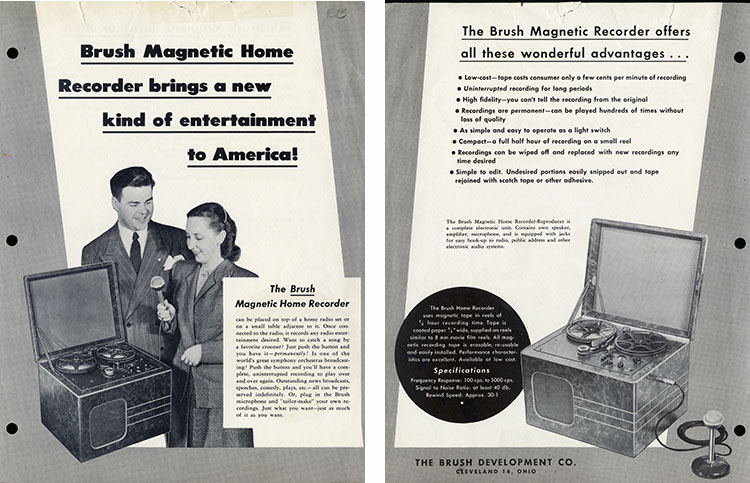

Brush Magnetic Home Recorder brochure, AC535-0000005-01 and AC535-0000005-02. S. Joseph Begun Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

In February 1946, a Brush Company publication heralded the introduction of recording technology for the home market. “Dr. S. J. Begun, in charge of most of the magnetic recording development work at Brush, explained that with the development of the paper tape medium and the high fidelity Brush Home Recorder, it is now possible for the first time for the average person to make home recordings of completely satisfactory fidelity and with no more skill than is required to switch on a radio or a vacuum cleaner.” (Brush Developments, February 1946, 1, 91, box 4, folder 10a, S. Joseph Begun Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History)

Semi Joseph Begun (seated, second from left), at an unidentified meeting, 1948, AC0535-0000004. S. Joseph Begun Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Learn more about Semi Joseph Begun’s life and work:

Explore the S. Joseph Begun Papers at the Archives Center, National Museum of American History

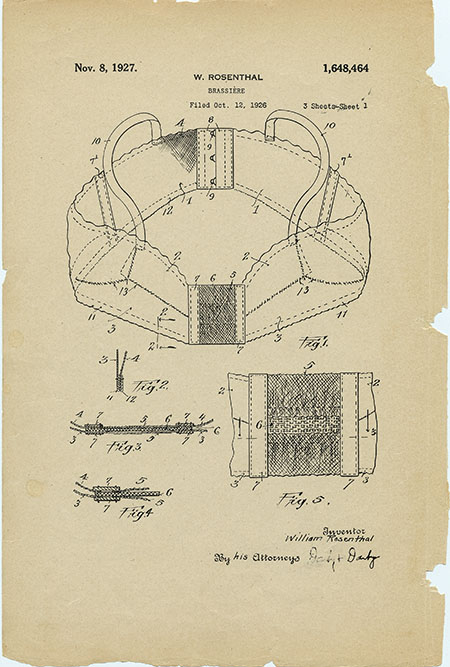

RUSSIA | Ida & William Rosenthal

Ida Kaganovich (1886–1973) and William Rosenthal (1882–1958) were born in Russia and met as anti-czarist protesters. They immigrated to the United States in 1905 and were married in 1906.

Enid Bissett, 1939, AC0585-0000011. Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Ida was a skilled dressmaker who disliked the simple lines and loose fit of the fashions that were popular for women in the 1920s. She and her business partner, Enid Bissett, designed a brassiere that gave their high-end dress customers a more natural shape. The undergarments were a success and Ida, Enid, and William founded what would become the Maidenform company in 1922.

By the 1930s, Enid had retired and Ida and William managed the company—she handled sales and finances and he created the designs. Maidenform remained in the Rosenthal family until 1997.

Ida and William Rosenthal, 1956, AC0585-0000055. Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

One of William Rosenthal’s early brassiere patents, US Patent 1,648,464, was issued in 1927, AC0585-0000090, Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Reflecting Ida Rosenthal’s commitment to a woman’s natural shape, William Rosenthal’s US Patent 1,648,464, issued in 1927, states that his design “is adapted to support the bust in a natural position, contrary to the old idea of brassieres made to flatten down the bust.”

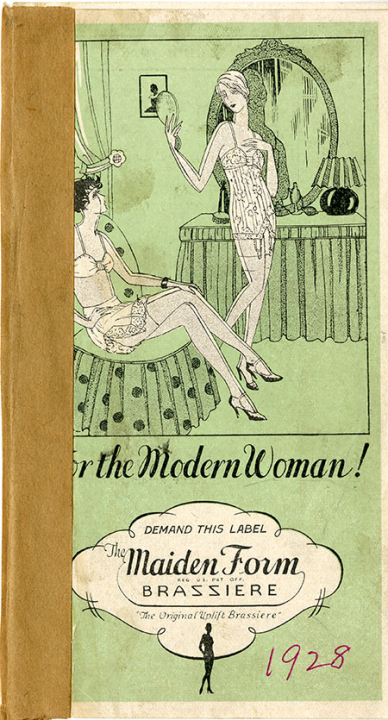

Maiden Form style book, around 1928, AC0585-0000098-01. Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Maidenform issued a range of style books that helped store buyers select merchandise and place orders. Each book includes the styles offered for the season or year, wholesale and retail prices, and the colors and sizes available.

Workers in the finishing department of the Bayonne, New Jersey, Maidenform plant, 1939, Box 2, Folder 1, Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Maidenform’s original factory was in Bayonne, New Jersey, but the company eventually expanded to plants in West Virginia, Florida, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic.

Operator sewing on a multiple needle machine, about 1941, AC0585-0000101. Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Workers at sewing machines in the Bayonne, New Jersey, Maidenform plant, May 1956, AC0585-0000102. Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

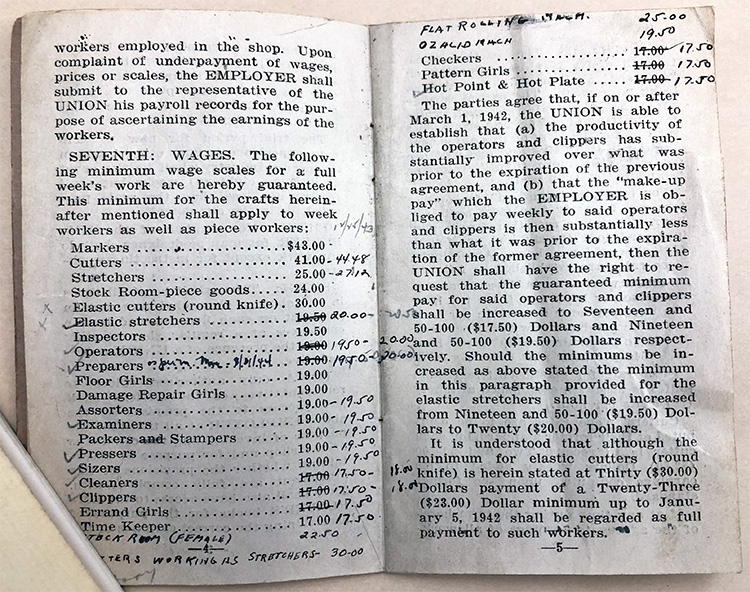

Many Maidenform employees were members of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. Agreements between the company and the union stipulated wages and other working conditions.

The 1942 agreement between Maidenform and the union stipulated wages for various jobs. Maidenform Collection, Box 58, Folder 5, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Agreement by and between Maidenform, Inc., and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, 1960 , AC0585-0000052. Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

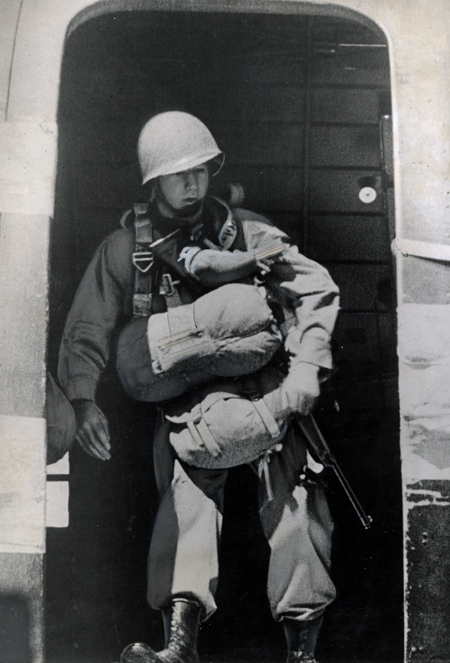

A paratrooper, with a pigeon in a vest attached to his chest, stands in the hatch of an airplane, 1940s, AC585-0000030. Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

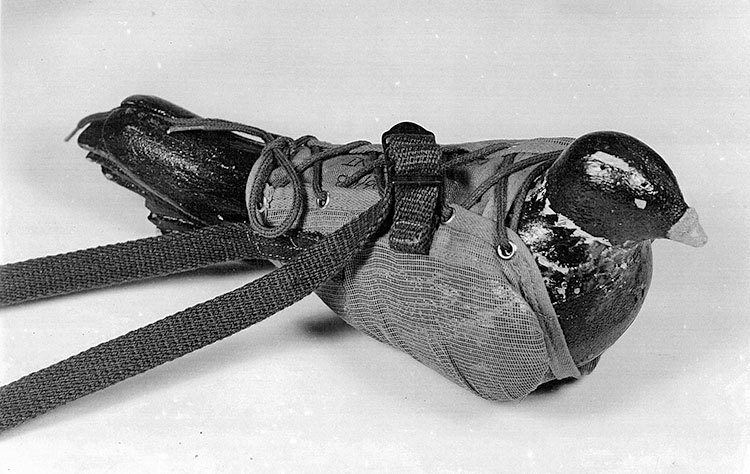

During World War II, Maidenform designed and produced vests for homing pigeons, so paratroopers could carry the birds with them as they parachuted behind enemy lines. Maidenform also manufactured silk parachutes in support of the war effort.

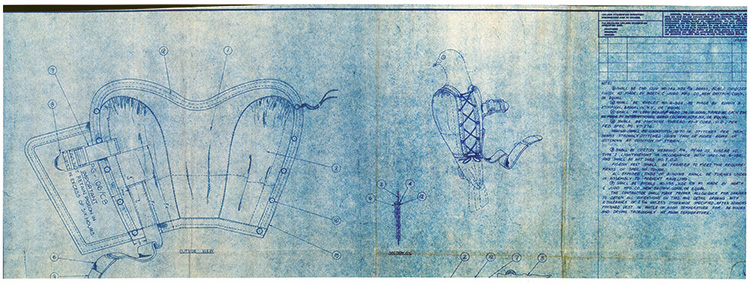

Blueprint for pigeon vest assembly, 1944, AC0585-0000033. Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Maidenform pigeon vest on model pigeon, around 1944, AC0585-0000051. Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

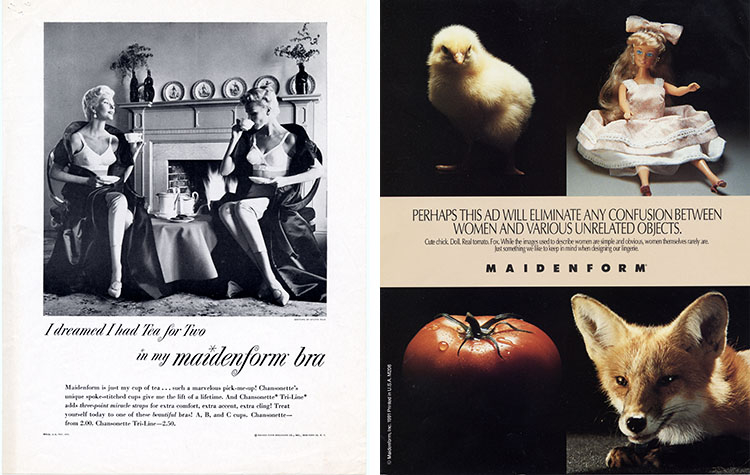

Maidenform was known for its innovative—and sometime controversial—advertising campaigns, beginning with the “I Dreamed” series launched in 1949. By 1992, the company’s tone had shifted, illustrated by the “Women’s Advocacy” advertisements.

Changing styles in Maidenform advertising: “I Dreamed I Had Tea for Two,” 1950s, and an ad from the “Women’s Advocacy” campaign, 1991, AC0585-0000084 (left) and AC0585-0000062. Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Learn more about Ida and William Rosenthal’s life and work:

- Explore the Maidenform Collection at the Archives Center, National Museum of American History

- Discover Maidenform objects in the collections of the National Museum of American History

- Dip into a database of US undergarment ads from Maidenform and other manufacturers from 1947–1970

SOUTH KOREA | InBae Yoon

InBae Yoon (1936–2014) was born in Korea and graduated from Yonsei University School of Medicine in Seoul in 1961.

Three years later, through a program that matched Korean medical doctors with United States hospitals and medical schools, Yoon immigrated to Baltimore, Maryland. He completed his internship and residency at Church Home and Hospital, specializing in obstetrics and gynecology.

Dr. InBae Yoon in the operating room, 1991. Courtesy of Kyung Joo Yoon

Dr. Yoon became fascinated with minimally invasive surgical techniques that promoted shorter recovery times and less scarring for the patient.

Dr. InBae Yoon performing laparoscopic surgery. Photo courtesy of Dr. Yue-Cheng Yang

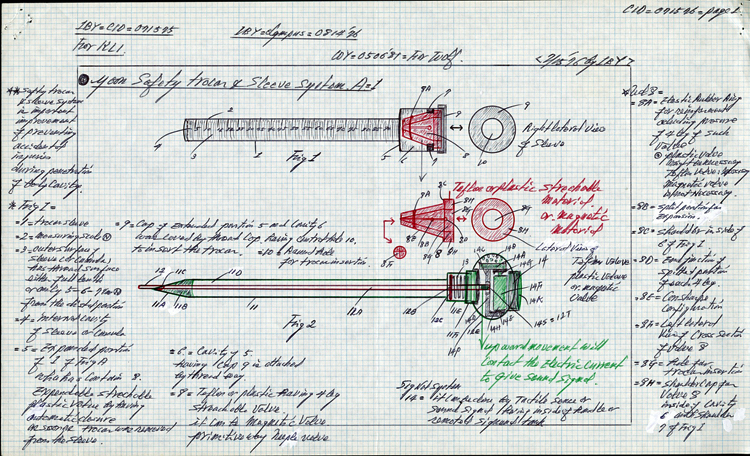

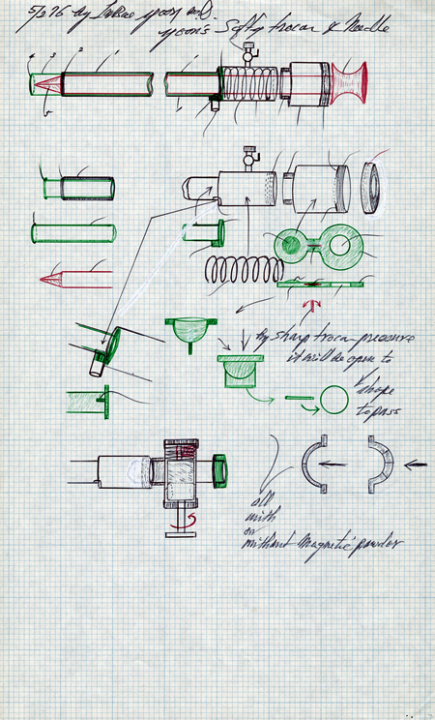

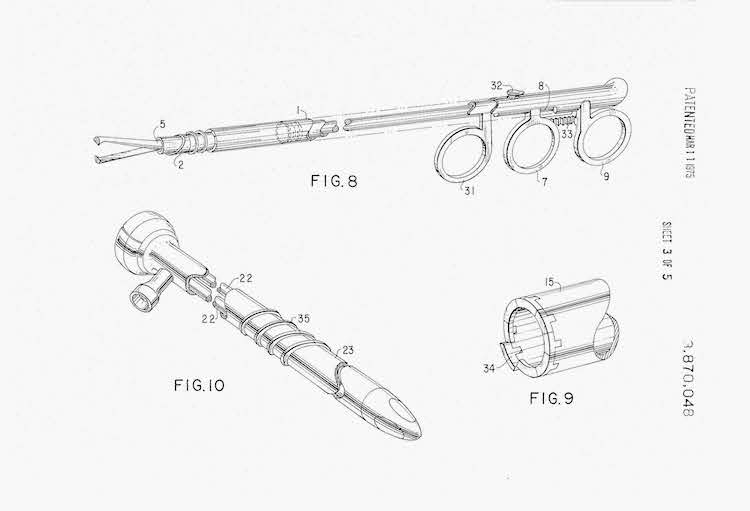

He began inventing devices for laparoscopic surgery, including safety trocars that create openings in the body and provide access for the insertion of other surgical instruments.

Drawing of safety trocar and sleeve system, by Dr. InBae Yoon, 1976, AC1414-0000006. InBae Yoon Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Sketch of safety trocar and needle, by Dr. InBae Yoon, 1976, AC1414-0000003. InBae Yoon Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Dr. InBae Yoon demonstrating his Falope-Ring applicator, undated. Courtesy of Kyung Joo Yoon

Dr. Yoon received more than 200 US patents for his inventions.

Dr. InBae Yoon received US Patent 3,870,048 in 1975 for a "Device for Sterilizing the Human Female or Male by Ligation.” Courtesy of USPTO

In the late 1990s, Dr. Yoon established the I.B. Yoon Multi-Specialty Endoscopic Research & Training Center at his alma mater, Yonsei University School of Medicine in South Korea. In his dedication address, he stated, “I dreamt of a clinical institute at Yonsei that would be equipped with the most advanced technologies, such as endoscopic or minimally invasive procedures, to improve patient care. I believe that physicians at Yonsei will take quantum leaps in medical care and practice based on the innovation and integrity I have already witnessed here.”

Dr. Yoon speaking at the I.B. Yoon Multi-Specialty Endoscopic Research & Training Center at Yonsei University School of Medicine in South Korea, 1998. Courtesy of Kyung Joo Yoon

Learn more about Dr. InBae Yoon’s life and work:

- Explore the InBae Yoon Papers at the Archives Center, National Museum of American History

- Read a tribute to Dr. Yoon written by former Lemelson Center head of invention education Tricia Edwards

- Check out objects from Dr. Yoon in the collections of the National Museum of American History