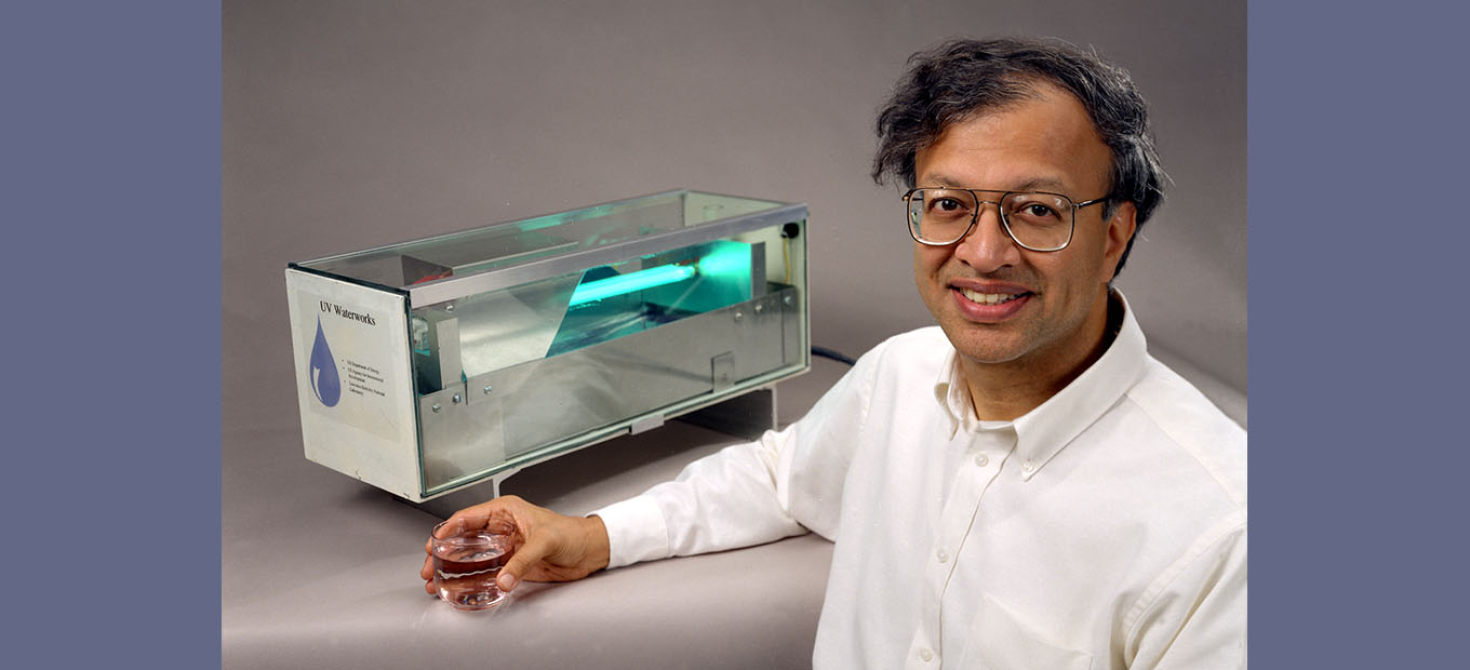

Every hour, more than 400 children in the developing world die from water-borne diseases. Now there is hope that many children's lives will be saved and the health of other children improved with the introduction of an innovative water disinfection device developed by Dr. Ashok Gadgil of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. UV Waterworks is a portable, low-cost, low-maintenance, energy-efficient water purifier that utilizes ultra-violet light to render viruses and bacteria harmless. It is also an outstanding example of an invention created in response to an urgent environmental health problem by a concerned and dedicated scientist.

On April 28, 1998, in keeping with its 1998 theme of inventing for the environment, the Lemelson Center hosted two events featuring Dr. Gadgil and UV Waterworks. First was a ceremony announcing the donation of two UV Waterworks units. One was presented to the National Museum of American History, where it will be a valued addition to the collection of objects on the history of public health. It was accepted by Dr. Ray Kondratas, Curator of Medical Collections. The other was donated to the U.S. Department of Energy for field testing at a site in South Africa where contaminated water poses a serious threat.

Dr. Arthur Rosenfeld of the Department of Energy received the gift and explained that the DOE was interested in the device for several reasons. While saving the lives of children is of foremost importance, the possibility of purifying water without polluting the environment is also a critical issue. By using ultraviolet light, powered by only 40 watts of electricity, instead of the more common method of boiling, which would require the daily burning of two or three tons of firewood to treat an equivalent amount of water, each UV Waterworks unit has the potential to prevent a ton of carbon dioxide per day from being released into the air.

The donation ceremony was followed by "Innovative Lives," the 14th in a series of programs in which the Lemelson Center brings middle-school students together with inventors to stimulate young people's creativity and their interest in science and invention. Gadgil met at the Museum with students from Jefferson Junior High School of Washington, D.C., and from Mary of Nazareth School and Nicholas Orem Middle School, both in Maryland. In connection with their visit, the students had been learning about municipal waterworks. Gadgil showed them the UV Waterworks unit and explained the process of its invention; then he accompanied them to the Museum's Hands On Science Center, where the students had a chance to experiment with water purification methods.

Gadgil told the students that as a child growing up in Bombay, India, he had a tremendous curiosity about how things worked. He knew from an early age that he wanted to be a scientist, always seeking to solve new problems. He obtained a degree in physics from the University of Bombay, but he found theoretical physics too abstract; he wanted to do science that would have an impact on the real world in his own lifetime. He went on to get a master's degree in applied physics from the Indian Institute of Technology and then, in 1979, a Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley .

After graduating, he was employed at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, researching problems of solar energy applications, energy efficiency, and indoor air pollution. While he enjoyed his work and was grateful for his training in the United States, where he learned the disciplined questioning and critical attitude that is essential to scientific inquiry, he wanted to apply his knowledge to problems in India. He returned to India and worked there from 1983 to 1988, but frustrated by the bureaucracy and petty politics he encountered in practicing science, he returned to Lawrence Berkeley, where he is now Senior Staff Scientist in the Environmental Energy Technologies Division.

One of the problems that concerned him in India was water contamination. When Gadgil was a child, five of his cousins died in infancy from diarrhea caused by water-borne organisms. Although he did not understand the implications of their deaths at the time, as an adult and a scientist he realized how heartbreaking and preventable those deaths were. In the back of his mind, even as he worked on other environmental issues, was the idea of finding a solution to this problem that so greatly affects India and other developing countries.

Although Bombay has a municipal water system and introduced chlorination early in this century, a large part of India's population still relies on open wells, rivers, or lakes for their water supply. The task of hauling water for daily use falls on women and children, who often carry water up to a mile from the nearest source. Women and children are also responsible for gathering firewood for cooking, a task that takes several hours a day and consumes much of their energy. It is not feasible for them to gather enough wood to boil their drinking water, and chemical disinfection is cumbersome and often impractical in communities without a water system. Even in cities like Bombay, where water is municipally treated and piped to homes, contamination frequently occurs.

It was a violent outbreak of cholera in 1993 that catalyzed Gadgil's determination to deal with the problem. A mutant strain of cholera had suddenly emerged in India and was resistant to existing vaccines. First detected in Bengal, it quickly spread. In the month of May, this disease killed 2,000 people in the state of Bihar alone. The epidemic soon reached the nearby countries of Bangladesh and Thailand.

Gadgil knew that of the three methods of water disinfection--boiling, chlorination, and exposure to a special range of UV light (which damages the DNA of viruses and bacteria so that they cannot reproduce)--only the third had potential for serving the very poor populations most affected by water contamination. He sent literature on UV disinfection to his colleagues in India, urging them to explore its practical application. When his colleagues protested that they did not have the time or funding to do so, he decided to take on the project himself, knowing that it would require working on weekends and evenings with whatever resources he could pull together.

With the assistance of a graduate student and the support of colleagues who lent him laboratory space and equipment, Gadgil began experimenting with available parts and materials. All existing UV water purifiers required pressurized water. To serve the poorest populations, his device would have to operate with unpressurized, hand-pumped or hand-poured water. To function in poor and rural areas, it would have to reliable, rugged, easy to maintain, and above all, cheap to purchase and use. No matter how effective the technology, it would be worthless if it did not fit easily into the social patterns and economic realities of subsistence-level communities.

Eventually Gadgil and his team obtained seed money from Federal and private sources and constructed a prototype. It met their goals of efficiency and low cost: it could disinfect eight gallons of water a minute for only two cents per ton. But made of stainless steel, it was large, heavy, and expensive. When they field tested it in a village in India (using a car battery as a power source, since the town did not have electricity), the villagers told them it was too efficient: it purified water in greater quantities and at a much faster rate than they could supply or use, and it was too big, bulky, and expensive.

So the unit was redesigned. Compact in size (28" x 15" x 11") and weighing only 15 pounds, the new model has no moving parts. It can disinfect four gallons of water a minute, enough to provide safe drinking water for up to 1,500 people, at a cost of only four cents a ton. It requires very little maintenance--just cleaning the water pan every few months and changing the UV lamp once a year. It uses less electricity than a table lamp and can be powered by a car battery, bicycle generator, wind, or even solar cells. The retail cost per unit is about $600.

This new model has been tested in India, the Phillipines, and Mexico and is currently being field tested at an orphanage near Durban, South Africa. With proper maintenance, it eliminates nearly 100 percent of pathogens from even highly polluted water.

Once the unit was developed, a number of companies expressed interest in manufacturing it. It was licensed to Waterhealth International, Inc. in Napa, California, and is now on the market. UV Waterworks has the potential to supply safe drinking water to communities around the world, not only in poor and developing regions, but anywhere that water treatment systems are not functioning, such as in the case of floods or other disasters. It has already received two awards: Discover Magazine's 1996 Award for Technological Innovation (Environmental Category), and Popular Science Magazine's "Best of What's New" 1996 Award.

Having found a solution to the problem he had set himself, Gadgil is now working on other environmental projects. In 1998, he will collaborate with UNICEF engineers in integrating the water disinfecting unit with a hand pump, all solar powered, so that people will not have to use water from open sources. He is also providing technical advice to India's largest bank concerning development loans to industries for better environmental management. His other projects deal with the effect of indoor air pollution on telecommunications equipment; energy efficiency in semiconductor high technology manufacturing; and a low-environmental-impact energy plant for Manaus, Brazil. With his intelligence, commitment, and determination, Ashok Gadgil will no doubt continue to fulfill his aim of using science to have a positive impact on the real world.