Kevlar® Inventor

“All sorts of things can happen when you’re open to new ideas and playing around with things.”

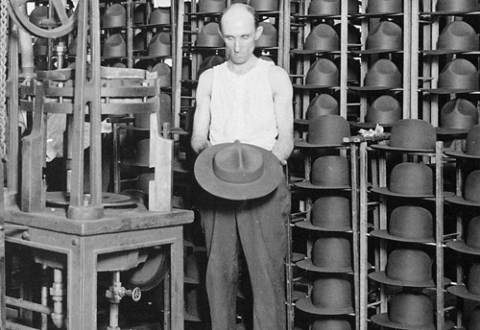

DuPont Textile Fibers Pioneering Research Laboratory. Left to right: Dr. Paul Morgan, Dr. Herbert Blades, and Stephanie Kwolek. Courtesy of DuPont.

One of the few women chemists at DuPont in the 1960s, Stephanie Kwolek’s work led to the development of Kevlar, a fiber best known for its use in bullet-resistant vests.

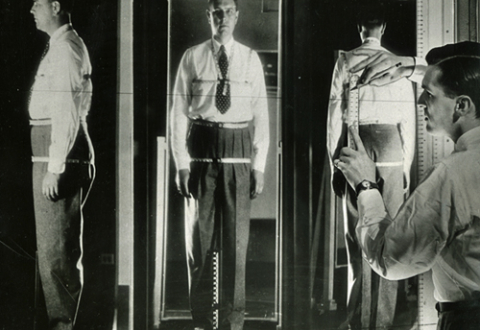

Kevlar manufacturing site in Richmond, Virginia, 1970s. Courtesy of DuPont.

Kwolek’s research at the DuPont Textile Lab included experimenting with long molecules called polymers in order to develop lightweight, heat-resistant fibers. One day in 1965, while trying to dissolve one of the polymers, something strange happened.

“Ordinarily a polymer solution sort of reminds you of molasses," she recalled, "although it may not be as thick. And it’s generally transparent. This polymer solution poured almost like water, and it was cloudy. I thought, ‘There’s something different about this. This may be very useful.'”

Convinced that this unusual solution could be spun into fibers, Kwolek spent several days urging her colleagues to spin it and test its physical properties. They were all amazed when the test results revealed how strong, stiff, and yet lightweight the fiber was.

From the time Kwolek first stirred that solution in a test tube, it took six years to produce Kevlar commercially. “It turned out to be a great team effort in the end,” she said.

How Strong is Kevlar®?

The polymer that Stephanie Kwolek created--Kevlar®--was very light but stiff and strong beyond anyone’s imagination. Pound for pound, Kevlar is five times stronger than steel. And it’s chemical and flame resistant. Today Kevlar® is used in boat hulls, bullet-resistant vests, cut-resistant gloves, fiber-optic cables, firefighters’ and lumberjacks’ suits, helmets, tires, sporting equipment--anywhere that resistance to heat or cuts is a must.

Kwolek in Her Youth

“I was always very good in math. Maybe that helped me later in science. My father was also very scientifically inclined. I guess I was genetically predisposed for the field I ended up in.

“When I was six years old, I wanted to be a fashion designer. I was fascinated with clothes. Designing clothes takes a lot of creativity, and I really liked to sew.

Stephanie Kwolek in the first grade. Courtesy of Kwolek family.

“I thought I would be a teacher. I spent a lot of time holding classes and teaching kids in my neighborhood. I also remember writing poetry and drawing. My father and I would go exploring in the woods, collecting flowers and leaves. I would press them in a notebook. We studied snakes and other things, too, as we walked through the woods.

“Later I got interested in science. I was either going to be a chemist or a medical doctor. When I got out of college, however, I didn’t have enough money to go to medical school.

“So I went to work as a chemist. The problem was that I was so interested in chemistry and research that I totally forgot about medicine.”

Stephanie Kwolek as a child on a family horse. Courtesy of the Kwolek family.

What's it like to be a woman inventor and scientist?

Stephanie Kwolek tells this story about when her patents for aramid fibers became well-known. "A chemist in another company said, 'That guy who did the work in the patents had to be a very outstanding chemist.' He referred to me as guy. It always surprised me, because at that time Stephanie was not a very popular name, so he must have thought Stephanie was a man's name, although I don't understand how he possibly could have thought it." Because the name on the front of the patent is her full name, it is hard at first to understand why that chemist thought Stephanie was a man. But, at that time, very few women were research scientists. Often, people assumed that anyone making important chemical discoveries had to be a man.

"At the time I was hired, it was not particularly an easy time for women, in particular for women involved with science. I do remember hearing and being told this by my professors in college: that a lot of women were coming back and going into what were considered women's fields. At one point, they thought they would discourage women from studying chemistry, but it took a number of years until women were more accepted. Even now, it is still not easy for women to be promoted into upper levels. But I think gradually they are getting there."

At the beginning of her career, Stephanie was one of only a few women who worked at DuPont as chemists. "When I was hired by DuPont," she explains, "a number of women who were hired by DuPont, about 12, they worked and produced until they married, when they had children, they left to take care of the children, as was the custom at that time." Sometimes this was difficult, but, Stephanie says, "I think one reason why it never particularly bothered me that there were so few women was that ... I thought of myself as a research chemist, and I considered myself equal to any of the other research chemists who worked in the lab." Polymer chemistry was such a new subject that it wasn't taught in schools. Everyone had to learn as they went along, and everyone, remembers Stephanie, "started on an equal basis ... I had to study up just as the men did. We helped each other and learned from each other. Somehow, I never set myself apart, or thought lesser of myself, because we all seemed to start on an equal footing."

Now, many women are researchers at universities and large companies, and many, like Stephanie, are busy inventing.

![The reverse side of the John Scott medal, inscribed, “THE SCOTT PREMIUM TO THE MOST DESERVING To John McMullin [sic] of Sinking Valley, Huntingdon County Penna. for a Knitting Machine 1835.”](/sites/default/files/styles/480w_x_330h/public/artifacts-franklin-medal-john-scott-reverse-0011-teaser.jpg?h=2a479378&itok=SfXxEB0j)