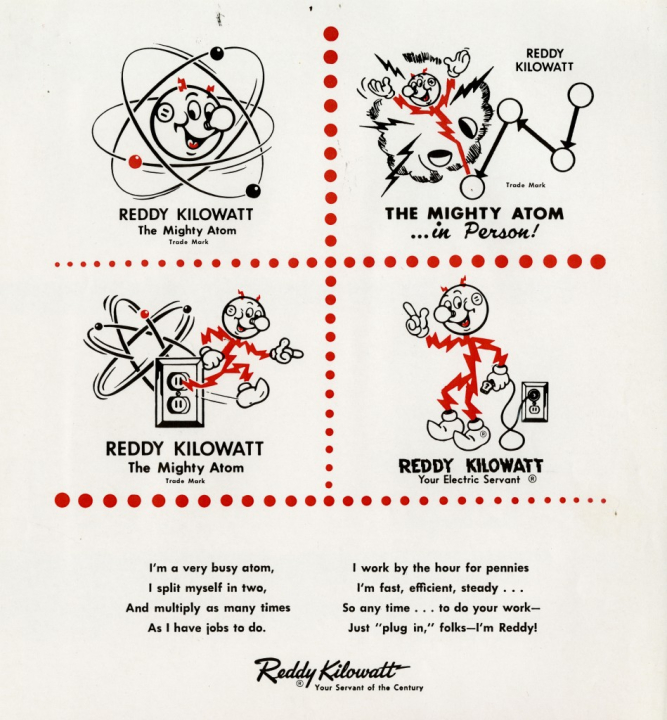

Pamphlet from the Central Illinois Light Co., July 1955. Source: NMAH Archives Center, AC0913-0000011.

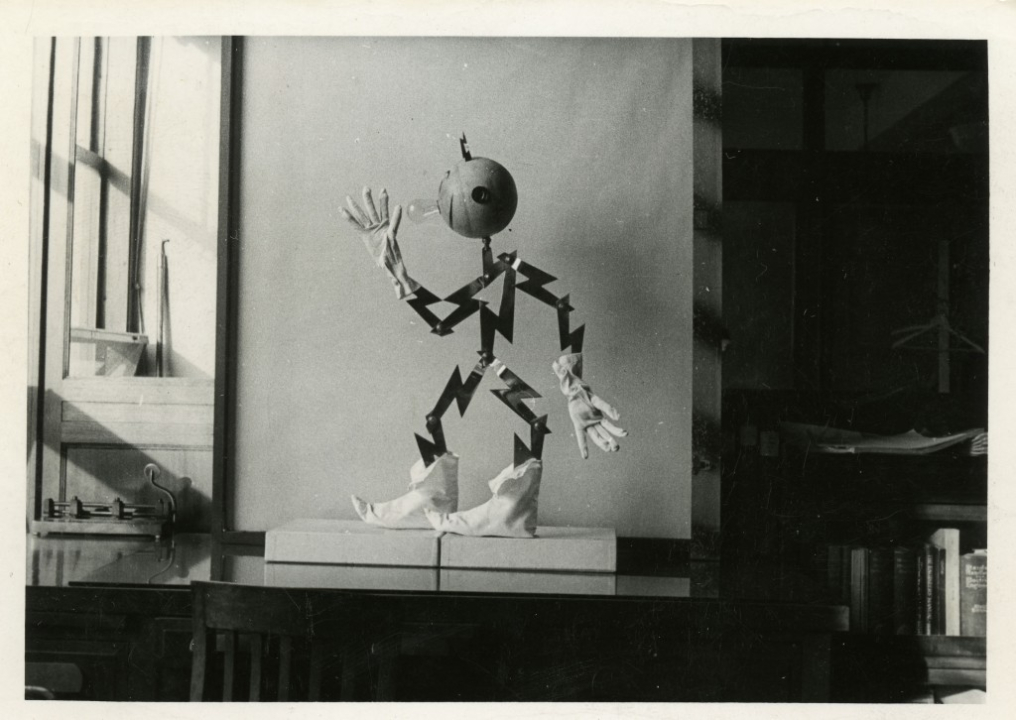

Photograph of Reddy Kilowatt (made of heavy copper), circa 1937. Source: NMAH Archives Center, AC0913-0000004.

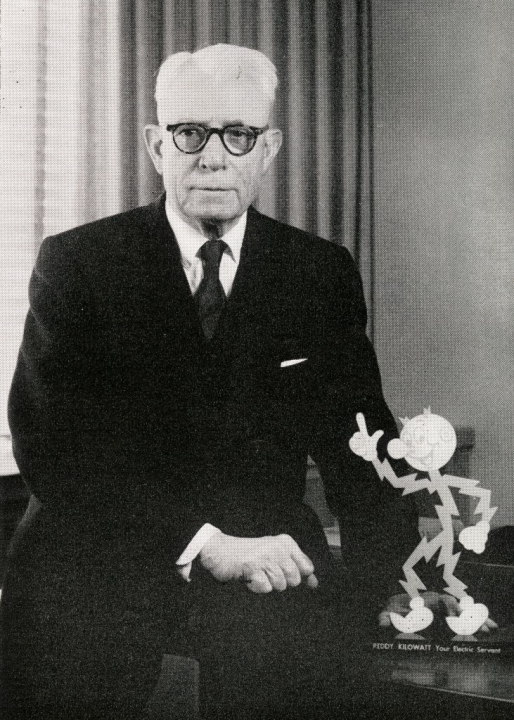

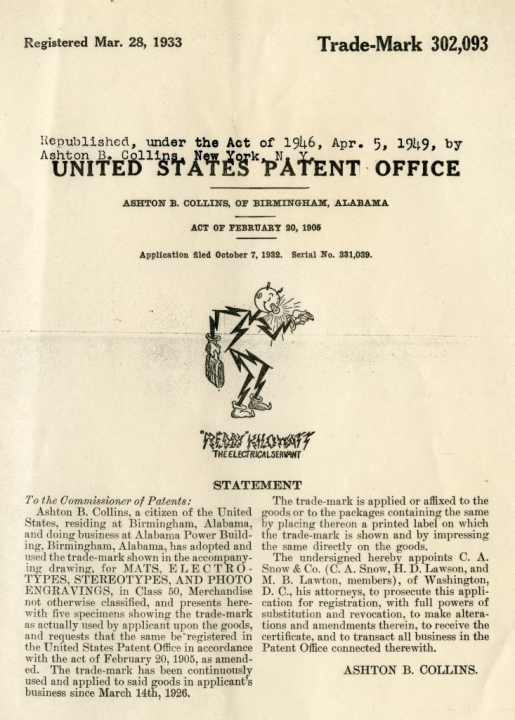

Reddy was the brainchild in 1925 of Ashton B. Collins (1885–1976), then commercial manager at the Alabama Power Company. The company was looking for a way to humanize electric service and Collins knew the figure needed to be appealing, clever, and able to tell the story of electricity easily. Through the talents of a company artist, D.J. Clinton, Collins’ vision of Reddy came to life. Collins copyrighted Reddy on March 6, 1926, and he debuted in a full page advertisement for the Alabama Power Company in the Birmingham News on March 14, 1926, and at the 1926 Alabama Electrical Exposition.

Image of Ashton Collins in NSP News, September 1962. Source: NMAH Archives Center, AC0913-0000003.

Letterhead of Ashton B. Collins, April 17, 1948. Source: NMAH Archives Center, AC0913-0000005.

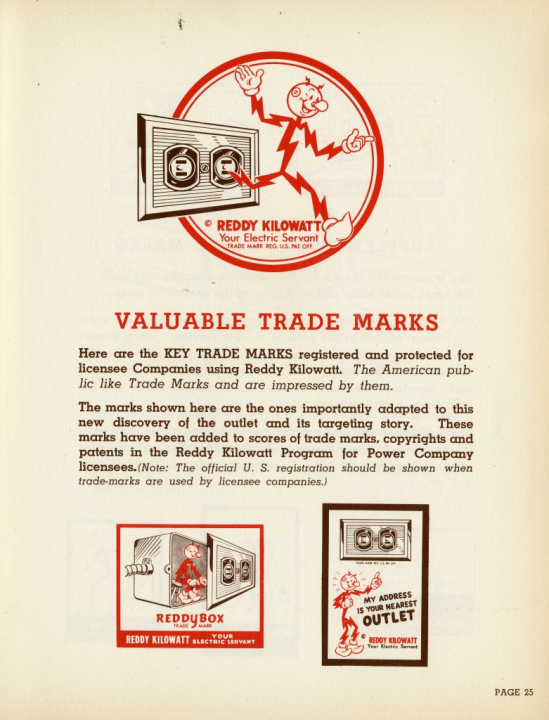

Collins worked tirelessly to develop Reddy into a comprehensive plan. By 1934 the company had launched the “Reddy Kilowatt Program,” targeted at investor-owned electric utilities. Collins wanted electric utilities to urge their customers to go “all” electric, using Reddy as the “pitchman.” The program included the use of trademarks and copyrights through the Reddy Kilowatt Service (clip art) and the Reddy News, which were sent to licensee companies to provide ideas about ways to use the Reddy Kilowatt trademark. The Philadelphia Electric Company was the first to adopt the program in January 1934. Other companies later joined, growing to almost 150 investor-owned electric utilities in the United States and in at least twelve foreign countries. Today, Reddy Kilowatt® and Reddy® are registered trademarks and service marks under Xcel Energy, Inc.

United States Trademark 302,093 for The Electrical Servant, March 28, 1933. Source: NMAH Archives Center, AC0913-0000008.

Valuable Trade Marks from The Master Link, Power Company Customers, 1944. Source: NMAH Archives Center, AC0913-0000009.

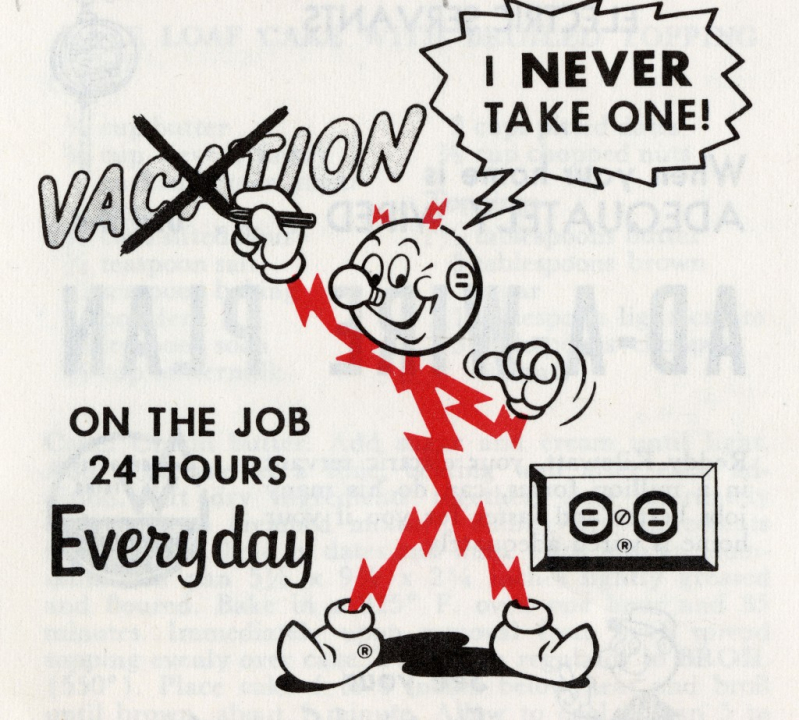

According to company literature, “Reddy was a cheerful, willing, and able servant.” Indeed, Reddy was “readily” available in homes, stores, businesses, and on farms across the United States. He was later adopted in other countries such as Canada, Mexico, Brazil, and the Philippines. In Brazil Reddy was known as “Zet” or “Joe” Kilowatt and in Portugal he was called “Faisca” or “Sparky” Kilowatt. But Reddy also provided benefits to the utility companies who adopted his program. He was able to explain the policies, programs, and service of the electric utility to its customers.

Advertisement reprint from Electrical World, May 20, 1957. Source: NMAH Archives Center, AC0913-0000007.

Booklet, At the Flick of a Switch, Interstate Power Company, circa 1946. Source: NMAH Archives Center, AC0913-0000010.

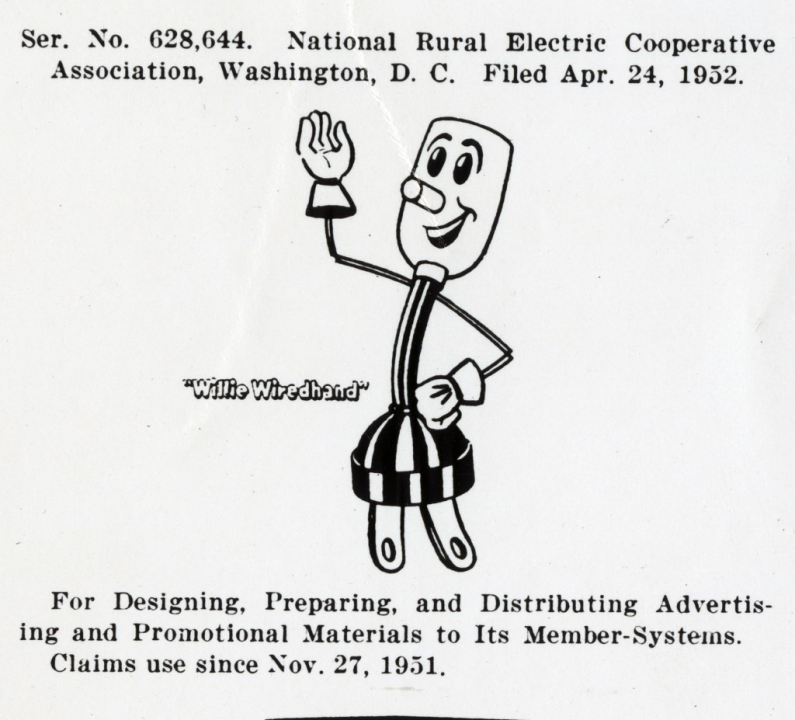

Reddy had some competition, though, from Willie Wiredhand, an advertising trademark character developed in 1951 by Andrew McLay during a national contest sponsored by the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (NRECA). Willie became an official service mark on April 24, 1952, promoting and endorsing consumer-owned electric cooperatives. On August 7, 1953, Reddy sued Willie. Reddy felt Willie “was confusingly similar in appearance,” but a judge decided that the trademarks were not in competition so Reddy had to share the electric limelight.

Willie Wiredhand advertisement for Sylvania light bulbs, Rural Electrification Magazine, No. 12, September 1957. Source: NMAH Archives Center, AC0913-0000012.

Exhibit from Reddy Kilowatt, Inc. (opposer) v. National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (applicant), August 1953. Source: NMAH Archives Center, AC0913-0000013.

United States Patent Office, service mark for Willie Wiredhand, June 9, 1953. Source: NMAH Archives Center, AC0913-0000014.

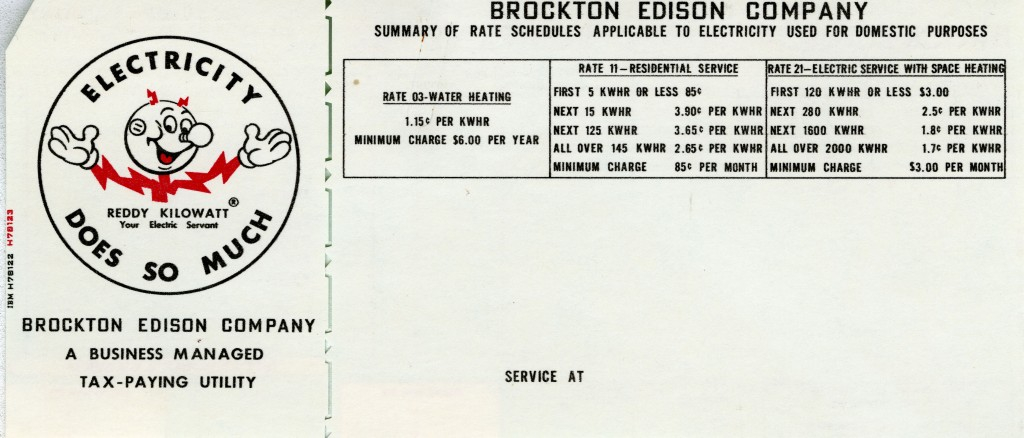

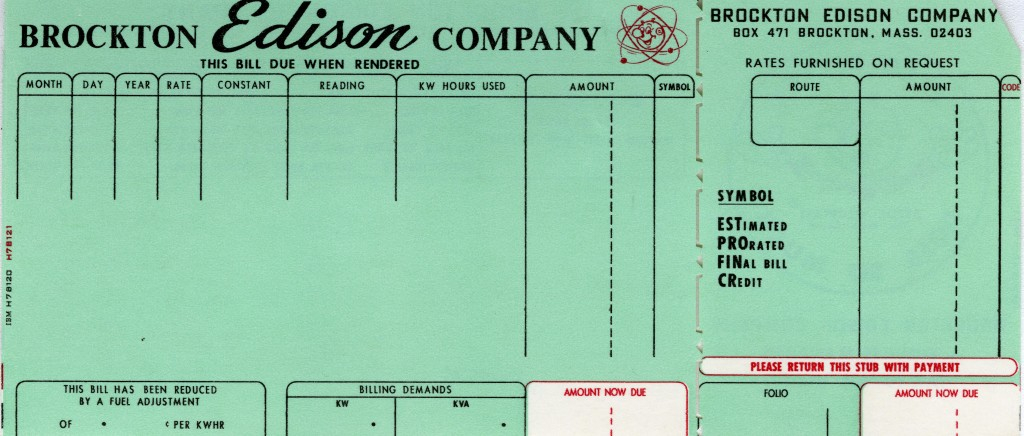

The personification of Reddy Kilowatt dominates the clip art, ephemera, and copyrights and trademarks the company obtained. He appeared on almost everything—matchbooks, pins, aprons, balloons, puzzles, books, novelty pieces, slides, films, trophies, posters, advertisements, and electric bills. It was the electric bill where Reddy was most visible, converting kilowatt-hours into servant hours. And consumers knew what a watt was worth: a section of the bill held a message from Reddy listing his monthly wages. Funny thing, they always equaled the amount of the bill.

Brockton Edison Company electric bill, circa 1956. Source: NMAH Archives Center, AC0913-0000006-02.

Brockton Edison Company electric bill, circa 1956. Source: NMAH Archives Center, AC0913-0000006-01.

To learn more about his service and the visually rich historic record documenting his electrifying life, visit the Archives Center and the Reddy Kilowatt Records. Other electronic-related collections that complement Reddy include: Louisan E. Mamer Rural Electrification Administration Papers; Electricity series, Warshaw Collection of Business Americana; Charles Came Collection; and the General Electric NELA Park Collection, to name a few.