Sherman Poppen, shown here with his Snurfer prototypes, thought his invention could be used for sport. His snow surfer ended up being marketed as a children’s novelty toy. AC159-0000001. Sherman Poppen Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History. © Smithsonian Institution

With sadness, the Lemelson Center notes the passing of two legends in the world of snowboarding in 2019—Sherman Poppen on July 31 and Jake Burton Carpenter on November 20. Their stories, as you will read below, are intertwined. Carpenter took inspiration from Sherman Poppen's Snurfer to create the iconic line of Burton Snowboards.

As a kid, snow surfing or “snurfing” was my favorite way to pass a wintry afternoon. I loved tearing down the hill, legs bent and arms stretched out for balance. I thought of my Snurfer the way I did a sled, and it never occurred to me that the Snurfer could be used as a piece of sports equipment. I had no idea that there was a fledgling community of enthusiastic riders in the US who raced one another to see who was fastest.

Many credit Sherman Poppen, the creator of the Snurfer, as the inventor of the snowboard. However, in examining his papers and early boards here at the Museum within the broader context of invention and sport, I learned that the historical record and prior patents attest to others before Poppen having the idea of a monoski to be ridden sideways like a surfboard or skateboard. Although he wasn’t the first to have this idea, Poppen was the first to commercialize it, in the mid-1960s.

Poppen owned a string of welding supply stores on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. On Christmas Day 1965, he braced two children’s skis together for his kids’ amusement, and then had the business acumen to immediately realize he was onto something. Within a mere few weeks he had a workable prototype, essentially a waterski with non-skid material to stand on and a rope lanyard to hold onto for better balance.

Poppen’s first prototype of the Snurfer resulted from bracing children’s skis together and removing the bindings, 1965. NMAH 2009.0092.01.© Smithsonian Institution; photo by Hugh Talman, ET2010-25770

He found that his invention worked regardless of the snow conditions. As he noted in a diary entry, “Snurfboard appeared to work effectively on hills where sled and saucers were useless.”1 The positive feedback, support, and suggestions from family, friends, and neighbors motivated him to improve upon and work toward selling his idea.

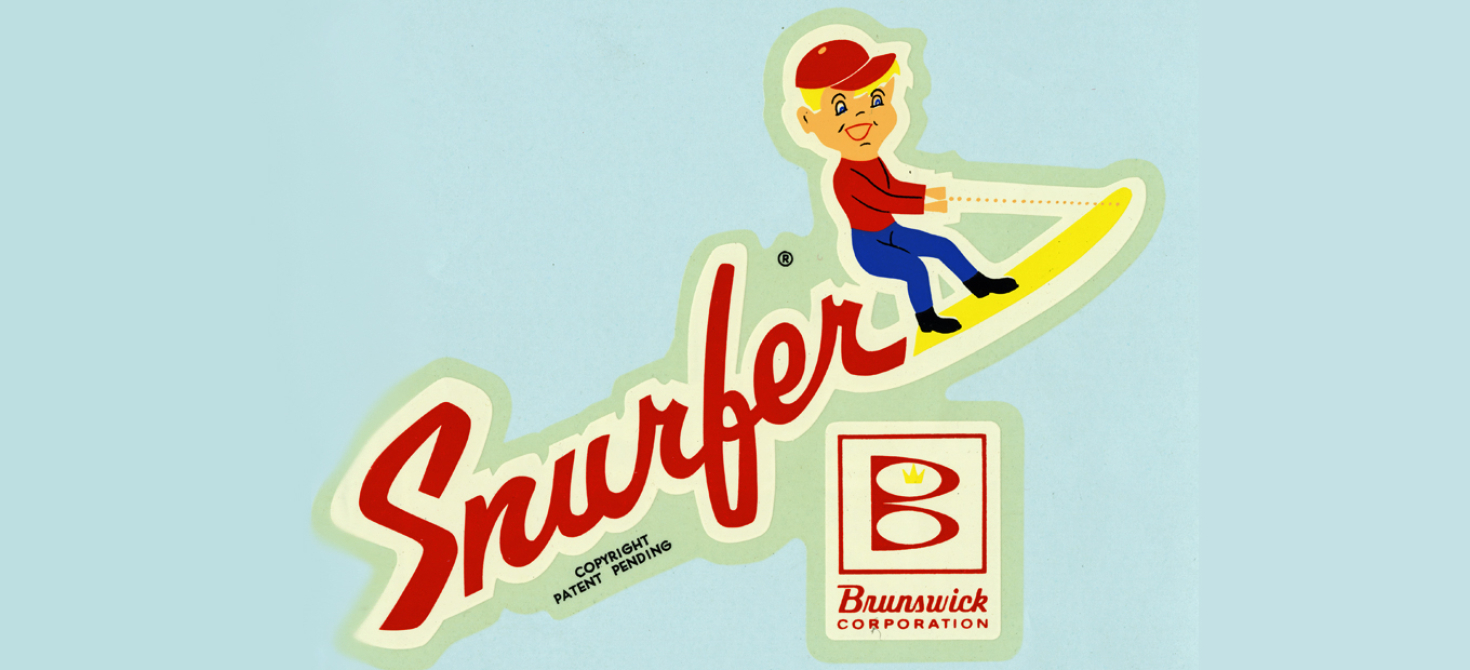

Poppen showed his friends who worked for billiard and bowling equipment manufacturer Brunswick. His timing seemed perfect: the company was starting a new consumer products division. Poppen met with Brunswick executives, inviting them to try his invention as well as providing them with a promotional film of one of his daughters enjoying snurfing. Incredibly, just two months later Poppen had entered a licensing agreement with Brunswick and each had filed separate patent applications.

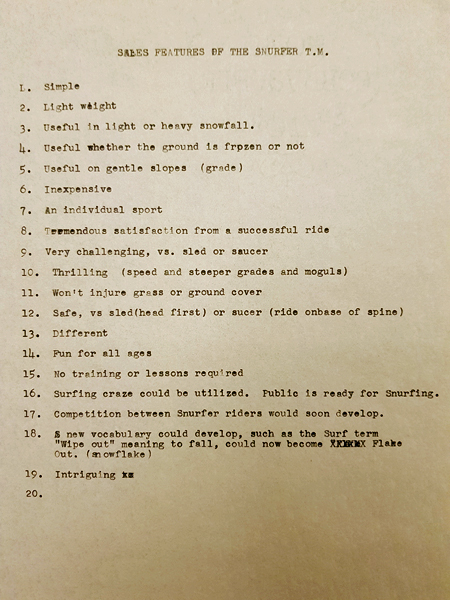

Being first to commercialize an invention is not without its pitfalls. While both Poppen and Brunswick saw the potential of the Snurfer as a piece of sports equipment, the company decided to market the product as the “hoola-hoop of wintertime,” as one executive put it. It is unclear whether Poppen initially disagreed with Brunswick’s marketing, but, in a 1996 interview, he conveyed his displeasure, commenting that, “Brunswick did a very poor job of marketing. At the Harvard School of Business they use the Snurfer as a study case in school of how not to merchandise a product.”2

Sherman Poppen’s list of the Snurfer’s sales features, around 1966. Sherman Poppen Papers, Box 1, Folder 17. Archives Center, National Museum of American History. © Smithsonian Institution

At first, the company’s strategy seemed to pay off. By 1970, approximately one million Snurfers had been sold in the US, Canada, and Europe. But when sales thereafter began to decline, Brunswick did not revamp its marketing and distribution strategy. By 1972, Brunswick decided to focus on its core business—bowling and billiards—and stopped manufacturing Snurfers.

Production soon resumed under the JEM Corporation and it would seem the company more fully embraced Poppen’s dual vision of the Snurfer, promoting the snow surfer not only for recreational use but also for competition. JEM revamped their product literature in acknowledgement that the Snurfer was being used not only by kids like me as a novelty toy, but also by thrill-seeking teens and those in their twenties who raced the snow surfer in downhill and slalom competitions. A newly designed brochure featured a competitive snurfer; the lead sentence read, “Tournaments are held with it.”

In 1978, JEM applied for a patent for improved non-skid foot treads and an adjustable length lanyard, features to enhance competitive performance. At the annual snurfing competition held near where Poppen lived in Michigan, the company awarded $1,000 in prize money and planned to promote snurfing as a sport through an expansion of local and regional competitions and the establishment of a National Snurfers Association. However, JEM did not follow through with these plans. Moreover, the general public continued to view the Snurfer as a toy. Without the company’s concerted efforts to change that perception, snurfing was not taken seriously as a sport except by a small community of enthusiasts.

Brunswick advertisement for the Snurfer that appeared in Boy’s Life, December 1966, AC159-0000009. Sherman Poppen Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History. © Smithsonian Institution

While things were not looking good for the future of snow surfing, there were athletes who had been inspired by Poppen’s invention. Paul Graves was one such innovator. Graves, a self-described “crazy kid who could do some interesting things” with the Snurfer, was sponsored by Brunswick and later JEM, giving demonstrations and promoting snurfing. At the 1979 competition, Graves showcased his unconventional snurfing techniques, performing surface 360s while racng downhill and ending his run with a front flip dismount. Graves’s novel use of the Snurfer in competition prefigured freestyle snowboarding.

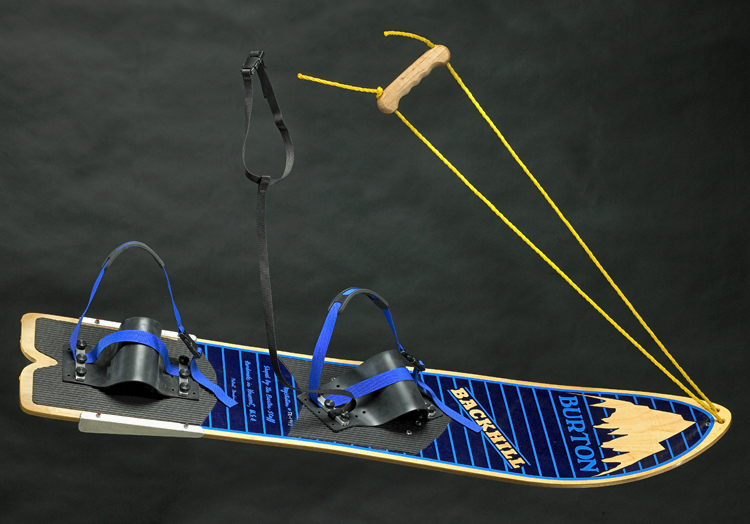

Rather than rethink snurfing technique, Jake Burton Carpenter considered the Snurfer itself. In 1977 he started the Burton Snowboards company in Vermont to make a product that would perform better than Poppen’s. The Backhill, the first he produced, was the result of prodigious experimentation and 100 prototypes. At the same 1979 competition where Graves wowed with his innovative technique, Carpenter showed up with his Backhill. It was wider than the Snurfer and had heel straps to secure both feet. Competition rules did not preclude the use of other boards and event organizers created an open division, which Carpenter won.

Thus began the influx of better designed boards that came quickly to supplant the Snurfer in competition. Carpenter later commented, “I always felt there was an opportunity for it [the Snurfer] to be better marketed, for serious technology to be applied to it, so Snurfing could become a legitimate sport instead of a cheap toy. I knew there was an opportunity there. I couldn’t believe Brunswick never took advantage of it.”3 While JEM’s product research and development flatlined, Carpenter, Tom Sims, and other manufacturers steadily refined the design of their boards, improving riders’ performance.

JEM brochure for the Snurfer, undated, AC159-0000002. Sherman Poppen Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History. © Smithsonian Institution

As Poppen began to lose control of the technology he had first brought to market, he also lost his influence on the burgeoning sport of snow surfing. The inventor had trademarked the word “snurfer” and various derivatives, which became problematic as other boards became available and used in competition. Poppen recalled, “When he got started and Burton was calling his board Snurfboards, and mine was a Snurfer, and I didn't like that because he was taking my [product] name away and I hired an attorney to tell him that, hey, that name is trademarked. Well, I wish I hadn't done it now, because that's when the sport became snowboarding. He couldn't use the word Snurfer or Snurf anywhere in his stuff so he called it the Burton Snowboard and that kicked off the whole sport.”4

In addition to improving snow surfing technique and equipment, Graves and Carpenter evolved the sport by organizing and promoting competition. While JEM continued to sponsor the National Snurfing Championship in Michigan, an event with primarily regional appeal, in 1982 Paul Graves and other competitive snurfers organized the National Snow Surfing Championships at Suicide Six ski resort in Vermont, with Burton Snowboards as a major sponsor. The more competitive racers attained speeds in excess of fifty miles per hour. At that velocity, riding on a Burton or a Sims board—both of which had bindings—provided a significant advantage over the Snurfer. Not only did the event succeed in attracting 125 athletes from across the US, it drew national attention, with mentions on both the Today Show and Good Morning America.

The Backhill snowboard made by Burton, 1985, NMAH 2010.0240.01. © Smithsonian Institution; photo by Hugh Talman, ET2011-38364

Carpenter took over from Graves organizing the major northeast snow surfing competition. Since Poppen enforced his trademark of “Snurfer” and variations of the word, Carpenter renamed the event the US Open Snowboarding Championship. With the rise of rival board manufacturers, JEM discontinued production of the Snurfer in 1983. Graves, whose board of choice was the Snurfer, worked with Poppen to find another interested manufacturer. Unfortunately, a licensing deal with the Daisy Corporation to produce Snurfers fell through and the venture was not pursued further.

Meanwhile, Carpenter actively worked to promote his snowboard manufacturing business and snowboarding not just as a sport but a lifestyle choice. In a coup, Carpenter allied with Stratton Mountain in 1985. Not only did the ski resort agree to allow snowboarding but also hosted the US Open Snowboarding Championship. That same year, the National Snurfing Championship in Michigan was cancelled due to a lack of competitors. No future snurfing competitions were held. Snurfing had given way to snowboarding.

Through the dogged advocacy of Carpenter and others, by 1990 most ski resorts in the US allowed snowboarders on the slopes. Terrain parks led to an increasing interest in technique. During the 1980s and 1990s, snowboarding went from a fledgling to a mainstream sport, making its debut at the Olympics in 1998. Although interest in snowboarding remains strong in the US, participation in the sport peaked in popularity between 2010 and 2011, with close to 8.2 million athletes.

Over the last ten to fifteen years, some snowboarders have opted to forgo foot bindings, out of a desire for a more fluid experience akin to surfing or skateboarding, and/or a greater challenge. This trend has led to a modest resurgence of interest in the Snurfer. In 2014, Poppen entered into a agreement with the company Vew-Do to manufacture classic Snurfers. Poppen learned his lesson, and this time allowed the trademarked name to be used for newly designed snow surfers. Other companies have begun manufacturing a snow surfer based on the Snurfer but with updated materials and design. Even Burton Snowboards offers a Snurfer-like board called the Throwback, which is similar to Burton’s initial Backhill model—except now it comes without bindings.

Researching the history of the Snurfer made me realize not only the importance of commercializing an invention, but also the difficulty inventors like Poppen face in maintaining control over the intellectual property of their creations. I hope Poppen, who passed away in July 2019, was gratified not only by his contribution to sport but also to recreation, as evidenced by the renewed interest in snow surfing and recent reissuance of the Snurfer. His archive does not contain much by way of fan mail, but Poppen must have been pleased to receive the letter of a snurfing enthusiast who confided to him in the early 2000s, during the heyday of snowboarding, “I will race anyone with a Snurfer but the delight of the product was not competition. . . . It was the mountain, the snow and the experience of floating. It was personal.”5

NOTES:

1 Sherman Poppen, “Diary of Progress on the Snurfboard,” [1966]. Sherman Poppen Papers, Box 1, Folder 17, Archives Center, National Museum of American History.

2 “You Should Thank the Man Who Built This Board,” Flakezine.com, 1996.

3 Michael Finkel, “Chairman of the Board Jake Burton Took a Childhood Toy and Launched an International Craze,” Sports Illustrated, January 13, 1997.

4 "You Should Thank the Man Who Built This Board,” Flakezine.com, 1996; Sarah Laskow, “Snowboarding Was Almost Called Snurfing,” The Atlantic, October 13, 2014.

5 Typed letter from Nick Johnson to Sherman Poppen, June 7, 2002. Sherman Poppen Papers, Box 1, Folder 1.