Dragon engulfed in blue flames. Artwork by Jason Monroe at Electric Anvil Tattoo in Brooklyn, NY, April 2019. Drawn from my request. This one hurt a lot! Photo by Seamus Heneghan

While helping to clean out the basement at my parent’s house, I stumbled upon some worksheets from when I was a kindergarten student. One sheet that particularly stood out to me was a questionnaire I had completed about my interests. I had checked the boxes for “soccer” and “art,” among several suggestions, but I laughed when I saw that I had also selected “other” and had written in “tattoos.”

It’s safe to say that I have had a lifelong fascination with tattoos. Although I wanted to get inked as soon as I turned eighteen, I waited until I was twenty-four years old. My first piece was a very small shell-like shape on the side of my ribs. Immediately, I was hooked. Four years later, I now have thirteen tattoos and counting.

At first, I refused to watch the artist work, and instead opted to shut my eyes and turn my head away from the tattoo’s placement area. Needles are scary! But I became curious once I got into the double digits—I finally began watching the artists at work on my body and was fascinated by the process. I began to wonder: how do tattoo machines work, and who invented them?

The art of tattooing has been around for centuries. Archaeologist W. M. F. Petrie found early tools dating back to 3000 BC, used to create tattoos at Abydos in Egypt. Petrie uncovered a sharp point, fixed in a wooden handle, and later discovered a set of small bronze instruments resembling wide, flat needles. When tied together, the needles would create patterns of multiple dots. Tattooed mummified human remains illustrate how these instruments were used to create permanent markings on skin by hand.1

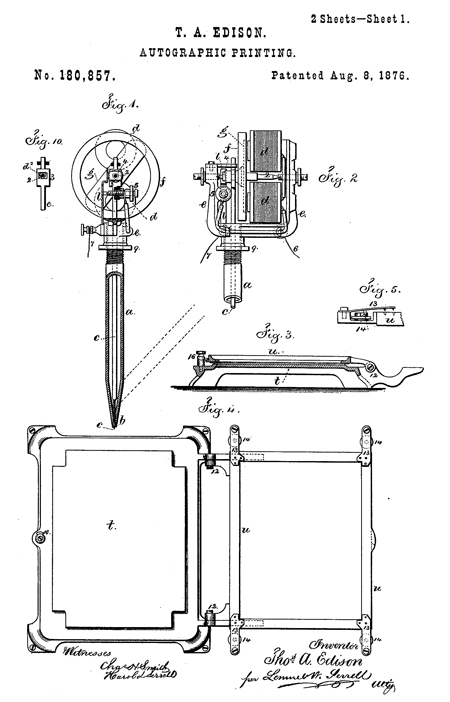

Thomas Edison patented a system of "autographic printing," a forerunner to the tattoo pen, in 1876. Courtesy of USPTO

Cut to 1876 when an inventor you’re probably familiar with—Thomas A. Edison—filed a patent for the electric pen, a machine used to cut stencils that were used with to make multiple copies of a document. It was one of the earliest applications of electric motors in consumer goods. The stem-mounted motor “drove a small needle up and down the shaft of the pen and created a stencil. The stencil was then placed in the press, and a roller was used to squeegee ink through the holes in the stencil, creating a copy of the document.”2

While Edison’s electric pen was a successful product, reaching markets across the US and globally, it later failed to compete against other models of mechanical pens that did not require batteries (Edison’s pen was powered by acid batteries). It seemed as though it was the end of the line for this particular invention.

Luckily for tattoo enthusiasts everywhere, the electric pen had a second life in the 1890s when Irish-American tattoo artist Samuel O’Reilly saw its potential and converted it into the first electric tattoo needle. On 8 December 1891, US Patent 464,801 was issued to O’Reilly for his machine that could puncture the skin to inject ink around fifty times per second, revolutionizing the tattoo industry forever.3

Irish-American tattoo artist Samuel O’Reilly saw the potential of Edison's invention and patented the electric tattoo needle in 1891. Courtesy of USPTO

Although regulated rotary motor machines like O’Reilly’s are still used, most of the machines for the modern art of tattooing are powered by electromagnetic coils, like the one pioneered by New York City-based artist Charles Wagner, who received US Patent 768,413 for his machine in 1904. Both rotary and coil machines move a collection of small needles up and down to puncture the dermis, or second layer of skin, inserting drops of ink between fifty and 3,000 times per minute. The spacing between needles is used to create different effects—if the needles are packed closely together, they will create solid lines on the skin; spread apart, they will create shading or coloring effects. Artists continue to modify and innovate their own machines to suit their needs and styles.4

Watching this process happen is so intriguing to me—the rapidly moving needles appear to push a flood of ink over the skin. It is when the artist wipes away the excess ink that you can see where it has been inserted precisely and deliberately.

Speaking of precisely and deliberately, my Mom gave me her precise list of reasons why I should not get tattoos and I have deliberately ignored that list—now I’m off to the shop! Sorry, Mom!

Notes:

1 Cate Lineberry, “Tattoos: The Ancient and Mysterious History,” Smithsonian magazine, 1 January 2007, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/tattoos-144038580/.

2 “Electric Pen,” Thomas A. Edison Papers, http://edison.rutgers.edu/pen.htm.

3 Emily Glynn-Farrell, “The Irish-American Who Invented the Modern Tattoo Machine,” The Irish Times, 16 October 2018, https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/abroad/the-irish-american-who-invented-the-modern-tattoo-machine-1.3634717.

4 Claudia Aguirre, “What Makes Tattoos Permanent?” TED-Ed lesson, https://youtu.be/DMuBif1mJz0.