The built environment that surrounds us is a serious matter, especially to Elaine Ostroff (1933–). An educator, advocate, problem solver, and innovator, Ostroff is one of the pioneers of the universal design movement who has advocated on behalf of the disabled throughout her career.

Universal design has its roots in the disability rights movement of the post-World War II era, when the number of disabled persons in the population increased, due both to the influx of injured veterans and to advances in medicine that enabled longer lifespans. The “Barrier-Free” movement of the 1950s arose from veterans’ demands to participate fully in the same educational and employment opportunities as the non-disabled. Over the next decades, as activists raised public awareness about disability rights, incremental legal and legislative changes were made, culminating in the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. New legal standards and regulations required the creation of barrier-free environments for the disabled.

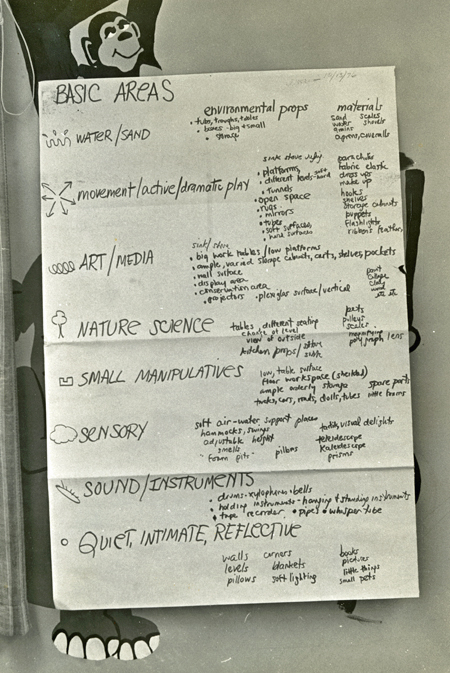

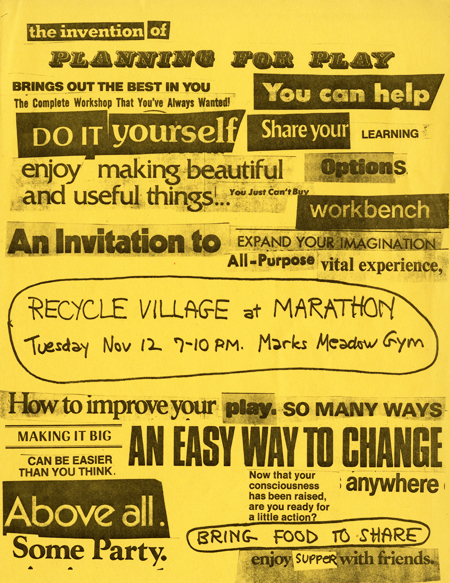

Poster listing basic areas of play for the Play Lab, about 1975 (AC1356-0000024). Courtesy of Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Proponents of universal design extended the idea to design environments that benefit everyone. In 1996 Ostroff said, "Universal design is an approach to architectural design that considers the entire range of capacities and potentials of people and how they use buildings and products throughout their lives. The approach goes beyond technical standards that provide only minimal accessibility in compliance with regulations and extends design to increase the capacities of men, women and children of all ages and abilities.”

Ostroff’s work has improved the quality of life for disabled persons—especially children—and the general population as well. Ostroff sees a problem, analyzes, reflects, learns, and presents a solution. Since the early 1960s, Ostroff has been involved with creating accessible environments on a national and international level. Her work with children began in 1962 when she founded the Looking Glass Theatre in Providence, Rhode Island. This touring theater company presented original, improvisational plays to children from all socioeconomic groups. Each performance was adapted to the setting in which it was staged—libraries, parks, community centers, playgrounds, and housing projects. At the Theatre, Ostroff rejected all the old ideas about theater design and made the productions more interactive and improvisational. Ostroff’s goal was to create a theater accessible to all. In her 1978 book Humanizing Environments: A Primer, Ostroff described the profound affect her work with the Looking Glass Theatre had on her work in Massachusetts schools for developmentally disabled children. “I began to see the potential of drama as a social force. We were demystifying theatre—there was no back stage, everyone could see our transformations and could participate in them. It was an open theatre; it was a context where many different people could get together. I learned about the power of transforming environments; how liberating it was to change a setting so that it supported another activity, and how that new setting communicated to other people.”

This 1974 flyer for a “Planning for Play” workshop held at Marks Meadow Elementary School on the University of Massachusetts, Amherst campus promoted the use of recycled materials in environments where children play and learn. “So I invented this whole thing,” Ostroff recalled in 2000, “of fixing the environments using recycled materials. We could make toys out of recycled materials and it wouldn’t cost any money. I became known as this person who did things with space” (AC1356-0000010). Courtesy of Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Ostroff applied these theater principles to her work in schools, transforming dreary spaces into safe play and learning spaces that inspired creativity in the students. Ostroff’s project 'Planning for Play," a graduate level education program that she started at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst in 1974, is an example of her innovative thinking. Combining play, the arts, and environmental design, the program sought to change the treatment of children—especially those with special needs—by transforming their classroom spaces. Among other things, Ostroff used recycled materials, such as foam and rubber, to soften the typically harsh classroom environment. This program was the first broad application of environmental design ideas in education training and was one of the first steps in raising teachers’ awareness that the physical environment influences learning.

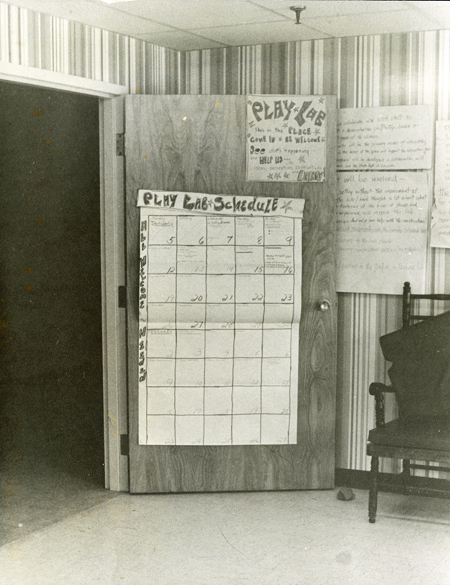

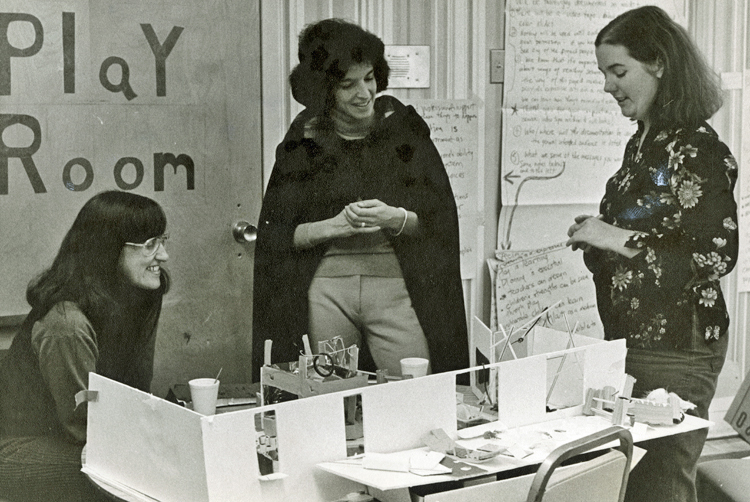

In 1975, the State of Massachusetts Department of Mental Health supported Ostroff and several graduate students from the University of Massachusetts School of Education with a grant to create the Play Lab in a renovated two-car garage. The lab was attached to a community group home for children with Down syndrome and was used to train human services professionals and as an educational experience for children. The space was designed for children to discover their abilities, to explore freely, using equipment such as tunnels and slides, building with recycled materials, water play, painting, dress-up, dancing, and exploring sound on their own and in structured activities led by staff. The lab was the direct opposite of the typical institutional setting. Ostroff said in a 1975 Massachusetts Daily Collegian article, “That’s the secret. If you make a place that’s really good for handicap kids, it’s good for everybody.”

Play Lab schedule, 1976 (AC1356-0000022). Courtesy of Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Building on her previous work, Ostroff co-founded with Cora Beth Abel the Adaptive Environments Center (now the Institute for Human Centered Design) in 1978 to confront the barriers that prevent persons with disabilities and older people from fully participating in community life. In 1989, with support from the National Endowment for the Arts, she developed the national Universal Design Education Project at Adaptive Environments, which sought to incorporate universal design in professional curricula.

Ostroff was inspired by Gunnar Dybwad (1909-2001), a prominent international advocate who fought for community living and the de-institutionalization of people with developmental disabilities and Raymond Lifchez (1932-), professor of architecture and city and regional planning at the University of California, Berkeley. She also worked closely with, and learned from, Ron Mace (1941-1998), FAIA, the architect who powered the accessibility movement through his personal experience of disability along with his architectural training and experience. Ostroff’s lifelong commitment to access for all people is preserved in the Elaine Ostroff Universal Design Papers at the Archives Center.

Elaine Ostroff (left) with staff in the Play Lab, about 1975 (AC1356-0000023). Courtesy of Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Sources:

- Elaine Ostroff and Geri Atkins, Humanizing Environments: A Primer: The Most Facilitating Environments for Children, Their Teachers and Families (Cambridge, Mass.: Word Guild for the Massachusetts Dept. of Mental Health, 1978)

- Wolfgang F. E. Preiser and Elaine Ostroff, Universal Design Handbook (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001)