Eggs come in six sizes—jumbo, extra-large, large, medium, small, and peewee—and in three grades—AA, A, and B (grades are United States classifications that rate the egg’s exterior and interior quality factors). According to the United States Department of Agriculture, egg production in the US totaled 9.66 billion during December 2021, which included 8.38 billion eggs headed for consumers’ tables ("Chickens and Eggs," January 19, 2022). That’s a lot of eggs laid, packed, and shipped.

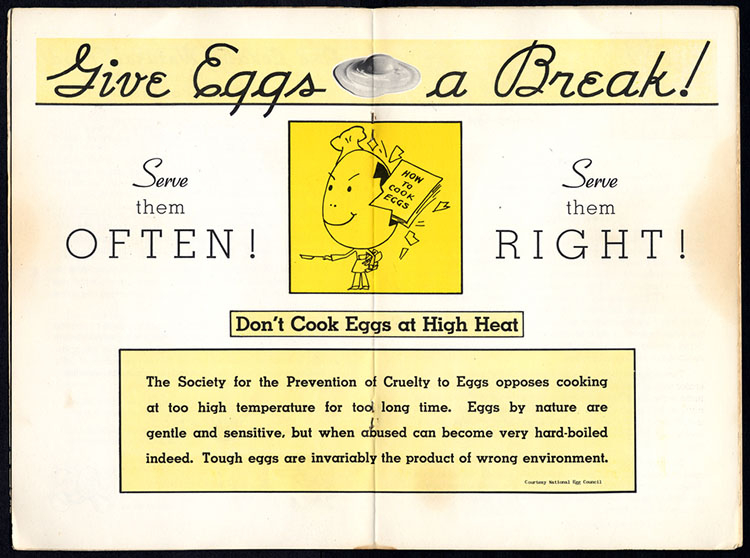

“Give Eggs a Break!” from What You Should Know about Eggs, The Whole Story in an Eggshell, New England Egg Fresh Egg Institute, 1940, AC1392-0000009-1. Jane and Michael Stern Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Eggs are a very breakable commodity that need to be treated well as they make their way to our grocery store shelves. Packing eggs properly has a significant economic impact, too. In the March 1921 issue of Printer’s Ink Monthly, it was reported that 67,000,000 cases of eggs were produced in the United States and were worth more than $1,200,000,000. The American Railway Express Company—a national package delivery service that operated in the United States from 1918 to 1975—noted that its egg breakage claims exceeded $100,000 a month and that much of the egg breakage was due to the use of inferior packing material (Printer’s Ink Monthly, page 83). By today’s standards, that would be a whopping $1.5 million in monthly breakage claims.

There are hundreds of patented egg carrier, egg case, egg basket, and egg carton inventions in the United States that sought to remedy the problem of how to get eggs from the farm to the consumer without breaking. Many egg ads used phrases such as “no losses,” “no more broken eggs,” “safest case around,” “stop your breakage losses,” and “why take chances?” to entice egg producers to use their packaging product for shipment.

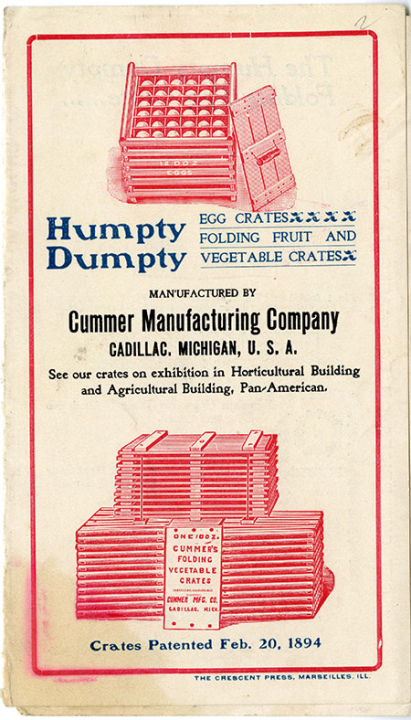

“Humpty Dumpty” egg crates brochure, Cummer Manufacturing Company, Cadillac, Michigan, undated, AC0060-0007659-02. Warshaw Collection of Business Americana, Series: Packaging, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

The modern egg carton that we find in the grocery store today is made either from polystyrene plastic or molded pulp/cardboard, which is a renewable, biodegradable raw material made from trees. It is typically a flat tray with an attached lid designed to hold 12 to 18 eggs, but eggs weren’t always packaged this way. Today’s egg cartons trace their origins to the early 20th century, with several individuals from Great Britain, Canada, and the United States contributing improvements to its appearance and ultimate popularity.

Before the molded paper egg carton appeared, there were baskets, tubs, and wooden crates or cases that toted, stored, and transported eggs, such as the aptly named “Humpty Dumpty” folding egg crate made by Cummer Manufacturing Company of Cadillac, Michigan. Canadian born Herbert Harvey Cummer (1860–1918) invented a crate (US Patent 515,196) in 1894 that became well known for its red top rail and for holding three, six, nine, 12, or 15 dozen eggs. Made of birch, beech, or maple wood, farmers and poultrymen would receive a shipment of eggs in a Humpty Dumpty crate and then “knock it down” and return it by mail. By 1906, Cummer decided to expand his production opportunities beyond Michigan and opened a plant in Paris, Texas, to manufacture the folding crates, which were also used for fruits and vegetables.

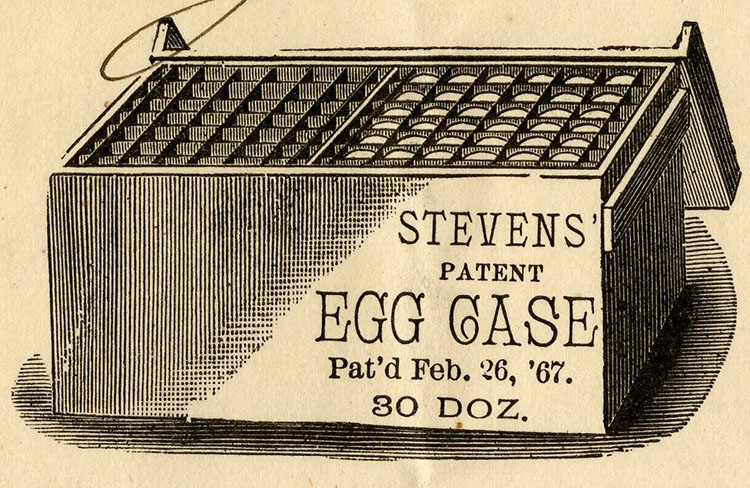

Standardization of the wooden egg case was introduced by John L. and George W. Stevens of San Francisco with their improved case for transporting eggs (US Patent 62,378) in 1867. The case was designed to hold 30 dozen (360) eggs, stored in 12 trays of 30 eggs each. Each egg had its own compartment with a separating horizontal diaphragm between each tier, from the bottom to the top of the case. Many wood crates and cases were filled with strawboard, straw, honeycomb, and other fillers to create a “cushion.”

James K. Ashley patented a case and box machine in 1902 (US Patent 695,364) that “expeditiously assisted in cleating the ends of egg-cases and making lids.” In 1925 Ashley patented his egg case machine (US Patent 1,544,878), an improvement of his previous machine.

Good packaging for eggs had many advantages, including less waste from spoiling, better handling, efficiencies in storing and display on store shelves, quicker sales with less weighing and wrapping, and standardization and uniformity. And, the package itself could advertise the product with printed logos and slogans of manufacturers and the selling agents.

Stevens’ Patent Egg Case, from masthead of receipt, John M. Duff Dealer in Fruit, Vegetables, Flour, Butter, Cheese, Eggs, Pork, Lard, Hams, and Poultry, 1884, AC0060-0007661. Warshaw Collection of Business Americana, Series: Packaging, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

As paper mills began to expand in the early 20th century, “Pulp-making became almost an independent branch of the [paper] industry, expanding into a business of great dimensions and serving many lines of manufacture quite aside from that of purely paper making” (Weeks, page 288). The first method for molding wood pulp appeared in 1890; in 1903, a machine to manufacture articles from molded pulp was patented by Martin L. Keyes (US Patent 740,023) from Cambridge, Massachusetts (Oliaei, Lindström, and Berglund, page 3). Keyes was a student of pulp and pulp products all his life. In 1903, he founded the Keyes Fibre Company in Fairfield, Maine, with a later expansion to Waterville, Maine, where he manufactured papyrus pie plates and continued to invent and patent machinery for molding pulp articles. “By the end of the nineteenth century there had come into existence an entire industry of makers of highly specialized machinery to put all sorts of products into cans, boxes, envelopes, jars, bottles, tins, and tubes bearing labels or printed images and message” (Porter, page 27).

New materials and better manufacturing methods were adopted by the egg industry. The first known modern egg carton is credited to Thomas Peter Bethell, a cardboard box manufacturer in Liverpool, England. In 1903, Bethell patented an improved method for packing eggs in carboard cylinders for transit by post or rail (UK Patent GB190221677A). According to the The Dairy (October 1900), Bethell was known for his prize-winning butter packages and “specimens of his postal boxes for perishable products of every description, folding cases for butter, cheese, and bottles, circular boxes and folding cardboard boxes of every description or for every purpose” (The Dairy, page 293). The Raylite Egg Box, created by Bethell, advertised that protection for high-priced eggs during transit was a great need and using a Raylite box “insures against breakage” (Poultry Guide, page 169).

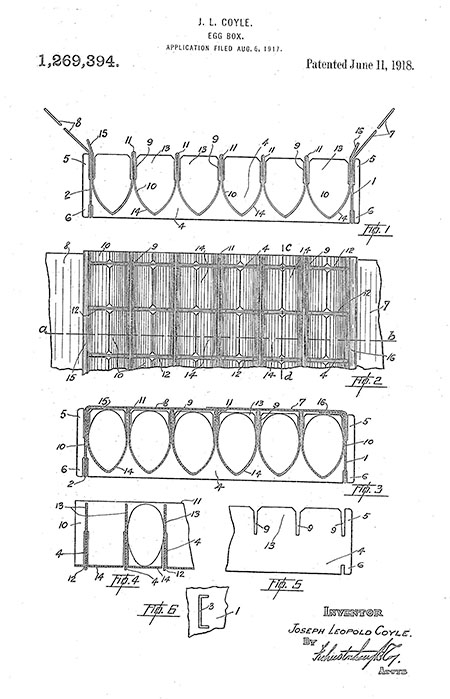

Canadian inventor Joseph Coyle patented his egg carton first in Canada (Canadian Patent CA181662A) on January 15, 1918, and in the United States (US Patent 1,269,394), on June 11, 1918. Courtesy of USPTO

One “paperman” who joined the ranks of the pulp industry was Joseph Leopold Coyle (1871–1972), a Canadian painter, surveyor, reporter, businessman (he founded the newspapers Omineca Herald, Bulkey Pioneer, and Interior News in British Columbia, Canada), and inventor. Coyle patented his egg carton first in Canada (Canadian Patent CA181662A) on January 15, 1918, and in the United States (US Patent 1,269,394), on June 11, 1918. It is widely documented that the invention was the result of a debate over broken eggs between a farmer and a hotel owner in the vicinity of Coyle’s newspaper office.

Known as the Coyle Safety Egg Carton, production began in Vancouver, British Columbia, with United Paper Products, and later moved to Los Angeles, where Coyle produced the carton himself under the name Coyle Paper Box Company. He then joined with Leon Benoit (1878–1957), a fellow Canadian, inventor, and businessman to produce the cartons in Chicago and New York under the name Coyle Safety Carton Company (also known as the Egg Safety Carton Company). Coyle would assign several of his patents to the company of which Benoit was president. Coyle expanded the production and manufacture of the carton to the Grant Paper Box Company (Indiana and Pittsburgh); in Toronto at the Colette Sproule Company; and in London, Ontario with Somerville Industries. In 1947, Robert Gair, Company, Inc., which had manufactured all of the Egg Safety Carton Company cartons from 1932 to 1944, bought the Egg Safety Carton Company (Confectionary Ice Cream World Weekly, page 32).

Building on Coyle’s work were Morris Koppelman (1872–1951?) and Francis H. Sherman. According to the 1920 United States Federal Census, Koppelman, a tailor from Russia, arrived in the United States in 1891. He invented a waistband (US Patent 729,072) in 1903 and a coat collar (US Patent 922,434) in 1909, selling the latter with his business partner, Leon Mann of the Leon Mann Company, under the name “Presto Collar.” How Koppelman made the jump from tailoring and clothes to egg packaging, I don’t know, but he was clearly inventive, patenting an egg-packing system in 1921 (US Patent 1,378,469); this was the first of a string of inventions for packing fragile articles). Sherman’s egg carton/carrier (US Patent 1,588,857) from 1926 facilitated automatic machine packing of eggs into the carton and resembled most closely the modern egg carton we see in the grocery store today.

“What Is an Egg?” by Mary Engle Pennington, in Eggs, edited by Paul Mandeville, for the “Century of Progress” world’s fair, Chicago, 1933. Courtesy of Google Books via Hathi Trust

No egg discussion would be complete without mentioning Mary Engle Pennington (1872–1952), chemist, bacteriologist, and refrigeration engineer. Denied a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from the University of Pennsylvania in 1892 (women weren’t allowed to receive degrees, only certificates!), she would eventually earn a PhD in chemistry from Penn in 1895 and have a significant and impactful career in food safety.

Harvey W. Wiley, the Chief of the USDA's Bureau of Chemistry, used his allocation from the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906 to hire food inspectors and to create the Food Research Laboratory. He encouraged his colleague and friend, Pennington, to apply for the position and lead the laboratory. Pennington’s academic and work-related experience made her the ideal candidate. Wiley received the Civil Service exam results (Pennington scored highest), changed her name to read “M. E. Pennington,” and offered her the job. When the Civil Service realized she was not a man, they told Wiley there was no precedent for hiring a woman. Wiley replied that there was equally no precedent for not hiring someone just because she was female. Pennington prevailed (Robinson, page 146).

Pennington wrote sections on “What Is an Egg?” and “The New Era of Cold and Cleanliness” for the two-volume set, Eggs, edited by Paul Mandeville and published for the “Century of Progress” Chicago world’s fair in 1933. She was issued five patents from 1912 to 1933 related to eggs and poultry. In Mothers and Daughters of Invention, scholar Autumn Stanley noted that “Pennington designed a new kind of breakage-reducing packing case” for eggs (Stanley, page 52; Yost, page 94). Although this design was never patented, Pennington’s work on refrigeration and her interest in safely transporting and storing perishable foods such as eggs most likely led her to consider egg packaging.

Now, once your eggs are safely home and have been enjoyed, you can reuse use the carton for insulation, sorting items, starting plant seedlings, holding paints, and even teaching arithmetic. That’s a lot of utility for one molded piece of pulp.

Sources:

- American Egg Board, accessed February 22, 2022, https://www.incredibleegg.org/.

- Barail, Louis C. Package Engineering. New York: Reinhold, 1954.

- Collins, James H. “Are We Trying to Build Good Will with Ersatz?” Printers Ink Monthly 2, no. 4 (March 1921).

- Confectionary Ice Cream World Weekly 38, no. 7 (August 15, 1947).

- The Dairy: A Monthly Journal for Dairy Farmers, Creameries, Dairymen, Cowkeepers, and All Connected with the Dairy Industry 7 (1900).

- The Irish Homestead, The Organ of Irish Agricultural and Industrial Development 18, no. 15 (April 15, 1911).

- “Leon Benoit, 79, Head of Egg-Carton Firm,” New York Times, September 11, 1957.

- National Utility Poultry Society. Poultry Guide and Yearbook. London, 1918.

- Oliaei, E.; Lindström, T.; Berglund, L.A. “Sustainable Development of Hot-Pressed All-Lignocellulose Composites—Comparing Wood Fibers and Nanofibers,” Polymers 2021, 13, 2747. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13162747

- Porter, Glenn. “Cultural Forces and Commercial Constraints: Designing Packaging in the Twentieth-Century United States.” Journal of Design History 12, no. 1 (1999).

- Reese, Chester. “Cashing in on Energy and Resourcefulness.“ The Dodge Idea, A Magazine of Industrial Progress 28, no. 8 (August 1912): 869.

- Robinson, Lisa Mae. “Regulating What We Eat: Mary Engle Pennington and the Food Research Laboratory.” Agricultural History 64, no. 2 (Spring 1990): 143-1953.

- Sherril, Lynn. “Who Invented the Egg Carton?” British Columbia Historical News 15, no. 3 (Spring 1982): 22-23. https://www.library.ubc.ca/archives/pdfs/bchf/bchn_1982_spring.pdf.

- Stanley, Autumn. Mothers and Daughters of Invention: Notes for A Revised History of Technology. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1993.

- United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, “Chickens and Eggs,” ISSN: 1948-9064, January 19, 2022. . Accessed March 3, 2022. https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/fb494842n/qb98nh31t/05742t71w/ckeg0122.pdf

- Weeks, Lyman Horace. A History of Paper-Manufacturing in the United States, 1690-1916. New York: The Lockwood Trade Journal Company, 1916.

- Yost, Edna. “Mary Engle Penington, The Greatest Authority on the Refrigeration of Perishable Foods,” chapter 5, American Women of Science (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1943): 80-98.

- Many individuals work simultaneously on inventions and ideas—a recurring theme in the history of invention—and the egg carrier was no exception. In addition to the individuals cited in this blog, others including Minnie J. Reynolds (Autumn Stanley, Mothers and Daughters of Invention, page 50), Harry R. Drake, Emile Daboval , Wybren R. Ferwerda, and Frederick R. Vernon also contributed ideas.