In Spark!Lab, we’re believers in the power of play to unlock innovation. While the old adage that “necessity is the mother of invention” may hold true, history also shows us that the desire to make life more fun, more exciting, or more pleasurable has led to a great deal of invention. These play-inspired innovations often have a wide-ranging impact beyond the seemingly trivial pursuits that spurred them.

Take, for example, celluloid—the first commercially-successful synthetic plastic. A century-and-a-half after its invention, synthetic plastic is an omnipresent material in our daily lives. Surprisingly enough, we have the popularity of billiards to thank, in part, for this building block of the modern world.

“Billiards on the Brain”

Although we often use the names synonymously today, nineteenth-century billiards differed from the game we call pool. Billiards referred to a range of cue games, some played on tables with pockets and some without. One popular version required only three balls—a cue ball for each player and one red striker ball. A player gained points by using his or her cue stick and ball to hit the striker into the opponent’s ball. The tables had no pockets. Instead, special bumpers called “cushions” surrounded the playing surface. Players used the cushions to make ricocheting trick shots, and more difficult shots earned more points.

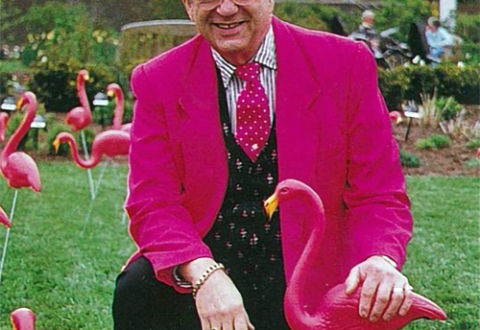

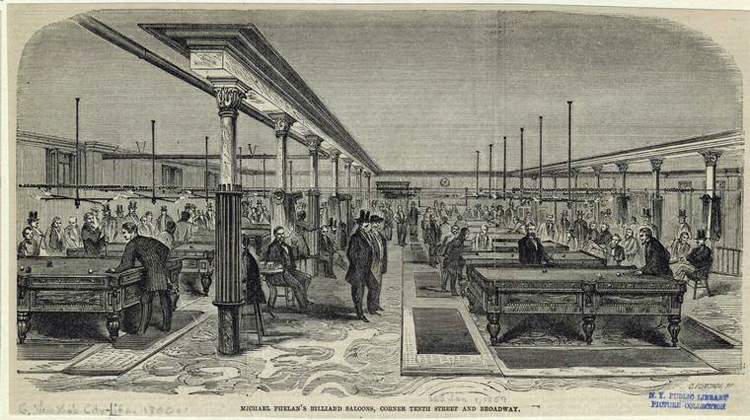

Michael Phelan's billiard saloons at the corner of Tenth Street and Broadway, New York City, 1859. Courtesy of New York Public Library

Billiards’ popularity grew rapidly in the nineteenth century. As cities expanded, so too did the number of billiard saloons where urban dwellers could learn and play the game. Some skilled players gained fame and fortune, and newspapers featured detailed coverage of high-stakes matches. In 1859, a crowd in Detroit supposedly watched Michael Phelan, a famous billiards player and promoter, for nearly ten hours straight—from 7:30 in the evening to 5:00 the next morning. Several years later, two composers captured the popular excitement for the game with a song called “Billiards on the Brain.”

In the midst of this billiards craze, players and businessmen made several improvements to the game’s equipment, including leather-tipped cue sticks and several types of rubber cushions. But one key item remained unchanged—the ivory billiard ball.

Ivory billiard ball, late 1800s, CL*329507, National Museum of American History. © 2016 Smithsonian Institution; photo by Richard Strauss, RWS2016-09965

Phelan described the ideal specimen in his 1858 book, The Game of Billiards: “The balls should be of a uniform size . . . Those of two and three-eighths in diameter, if made of the best East India ivory, close-grained and properly seasoned, will average a weight of seven ounces each, and are those best suited to the game.” “Seasoning” referred to the drying process. After hunters killed the elephants, harvested their tusks, and shipped them abroad, the raw material sat in warehouses for an extended drying period. Once ready, master ivory turners shaped the tusks into perfectly sized billiard balls (you can watch a video of these craftsmen at work here) and the balls were seasoned once again. Balls made of improperly seasoned ivory would crack or be damaged on impact.

Ivory gave billiard balls the right weight, roll, and rebound for the game. However, as Phelan lamented, the material was “dreadfully dear.” An average elephant tusk provided enough ivory for only four or five quality billiard balls. Businessmen like Phelan worried that the demand for the expensive and temperamental material might exceed the supply of elephants. He believed that “if any inventive genius would discover a substitute for ivory, possessing those qualities which make it valuable to the billiard player, he would make a handsome fortune for himself, and earn our sincerest gratitude.”

Inventing Imitations

As the oft-told story goes, in 1863 Phelan offered up that “handsome fortune” himself. His company, Phelan & Collender, advertised a $10,000 reward for a suitable replacement for ivory. An inventive-minded young printer, John Wesley Hyatt, saw the contest announcement, and his persistence in answering its call would eventually open the floodgates of synthetic plastic consumer products.

Hyatt patented his first attempt in 1865. He described his compound ball, consisting of a wood fiber core covered by a mixture of shellac and ivory dust, in US Patent 50,359. The new ball flopped, as players found it lacked the hardness and “feel” of real ivory.

Hyatt’s next idea came in 1868, when he found bottle of collodion had fallen over in his printing office. Printers used to material to coat their fingertips and prevent burns when touching hot lead type. The spilled liquid had hardened into a tough, clear solid. Hyatt thought collodion might make a better coating for his composite billiard balls.

The accidental discovery of hardened collodion fits neatly into the trope of serendipitous discovery so often heard in tales of invention. Hyatt’s efforts, however, did not end with a classic “Eureka!” moment. His story reminds us that invention is a process.

Hyatt tried to make a collodion-covered ball, but only found repeated failure. Undeterred, he switched his attention to one of collodion’s primary ingredients, cellulose nitrate. Highly-nitrated cellulose, also known as guncotton, is highly flammable—even explosive. Hyatt, who had no formal training in chemistry, spent a dangerous year experimenting with the material in a shed behind his home. Eventually he found that a particular preparation of guncotton mixed with camphor oil resulted in a strong, lightweight material that could be molded into almost any shape and dyed any color. He patented his “composition,” calling it “a good substitute for ivory in the manufacture of billiard-balls, and balls or articles of various descriptions, wherein it is desired to obtain toughness, hardness, and elasticity.” Shortly after, Hyatt and his brother trademarked the name “celluloid” and launched the Albany Billiard Ball Company to sell their new product.

An original celluloid billiard ball made by Hyatt’s company, CH*334572, National Museum of American History. The plaque reads: “Made in 1868 of Cellulose Nitrate, Celluloid. The Year John Wesley Hyatt Discovered This First Plastics Resin.” © Smithsonian Institution

Celluloid balls received mixed reviews. An 1872 article in the New York Times claimed that the composite balls could “hardly be distinguished from ivory balls” despite “cost[ing] about one-half the price ordinarily charged for ivory balls.” Even “such men as PHELAN and COLLENDAR [sic] of New-York were unable to withhold their testimony in their favor.” Yet in 1895, another writer insisted that “nothing has yet been found equal to ivory for billiard balls.”

Hyatt later reflected on some of the balls’ flaws, recalling, “A lighted cigar applied would at once result in a serious flame and occasionally the violent contact of the balls would produce a mild explosion like a percussion guncap.” He received “a letter from a billiard saloon proprietor in Colorado, mentioning this fact and saying that he did not care so much about it but that instantly every man in the room pulled a gun.”

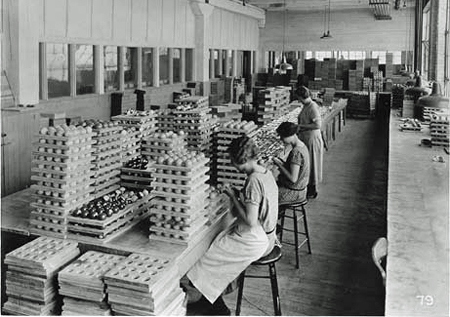

Celluloid billiard ball manufacture, 1920s. Albany Billiard Ball Co. Records, AC0011-0000001

Beyond Billiards

Despite its mixed record as a billiard ball material, celluloid launched a flood of other consumer goods. Hyatt’s company emphasized the power of celluloid to lessen people’s dependence and impact on natural resources. A promotional pamphlet declared, “As petroleum came to the relief of the whale,” so “has celluloid given the elephant, the tortoise, and the coral insect a respite in their native haunts; and it will no longer be necessary to ransack the earth in pursuit of substances which are constantly growing scarcer.” The ability to dye celluloid any color served to democratize rare and expensive materials through imitation. Manufacturers churned out celluloid corset clasps, shirt collars, cuffs, hair combs, brush handles, buttons, piano keys and eyeglass frames. In the 1880s, celluloid provided the base for still photographic film, and later for early motion picture film. Who would have thought the invention of movies depended on innovations in billiards?

Later iterations of synthetic plastics gradually replaced celluloid in most of its uses. Today, ping-pong balls remain one of the few celluloid products available on the market. Although its present-day use is limited, celluloid’s legacy looms large as the first in the wave of synthetic plastics that defined much of both work and play for twentieth and twenty-first century Americans.

For further reading:

Robert Friedel. Pioneer Plastic: The Making and Selling of Celluloid. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983.

Jeffrey L. Meikle. American Plastic: A Cultural History. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1995.