An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations tracks with early American history: first published in London in 1776, the first American edition was printed in 1789. Courtesy of Raptis Rare Books

In 1776, Adam Smith began his famous text, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, with what sounded like an anecdote. Describing the making of metal pins—then used widely to shred and comb fibers; in sewing, stitching, and tailoring; and for myriad other applications—Smith noted that a layperson would struggle to make more than a single pin in a day. A skilled craftsman working alone could make 20 pins. But driven by the “invisible hand” of market forces, pin making was characterized by a division of labor: “One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations . . . to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper [packaging].” Having visited a pin manufacturing shop, Smith described 10 workers producing some 48,000 pins in a day, a major productivity gain over craftsmen working individually.

Out of his observation of pin making in the 1770s, Smith deduced two points that are at the center of present-day discussions and debates over technology, innovation, and employment. First, invisible market forces are fundamental to the organization of work and the kinds of jobs available at a given historical moment. Second, changes in the organization of labor have tremendous economic benefits as products get cheaper and consumers can buy more. Lower-cost products can stimulate more consumption leading to more job growth. Starting in the 1820s, innovations in mechanization would impact employment in ways unforeseen by Smith, but congruent with his theories. Breakthrough technologies led to both job creation and job destruction, a process that would come to characterize the next 200 years.

Some fifty years after the Wealth of Nations was published, inventors on both sides of the Atlantic were building machines to automate pin making. The complexity of the process proved a challenge, but in the course of the 1830s, numerous patents were issued for machines that initially failed to work on a larger scale. For example, the American inventor John Ireland Howe spent over a decade experimenting with different ideas for pin-making machines after watching the indebted residents of the New York Almshouse laboriously make pins by hand. His persistence eventually paid off when Howe developed a unique rotary process to make pins with a solid head from a single piece of wire. The patent on his machine was issued in 1841 (see the photograph of his patent model at the top of this page).

With the backing of New York merchants, Howe had founded the Howe Manufacturing Company in 1833. The company moved to Connecticut in 1836, and grew quickly after his success with the pin making machine. By 1845, Howe employed 70 workers overall and had sales of $60,000 ($1.85 million in 2017 dollars). Alongside other metal products, Howe’s firm made over 70,000 pins daily on three of his machines. By 1860, improvements machinery used to package pins (a low-skill specialization already called out by Adam Smith in 1776) reduced Howe’s workforce to 36; employment as a “pin sticker” effectively ended.

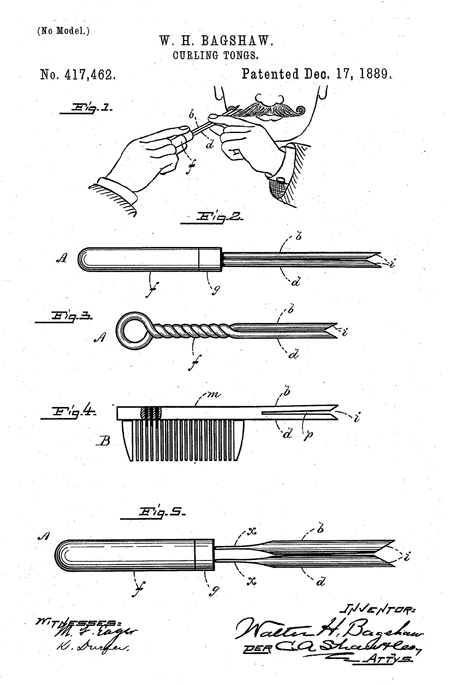

In 1889, Walter Bagshaw was granted US Patent 417,462 for an improved mustache curler manufactured using machinery similar to pin makers. Courtesy of US Patent and Trademark Office

Other inventors developed machines that made pins through other processes, or carried out additional manufacturing steps. For example, Walter Bagshaw, a British pin maker who emigrated to the United States in the late 1850s, learned about new approaches to mechanization in the rapidly industrializing city of Lowell. He founded his own firm—the Bagshaw Company—in 1870. In addition to textile pin making, Bagshaw patented machines to produce combs, curling tongs (used by men on their mustaches), shoddy pickers (used to separate useable thread from cloth in recycling) and other tools and instruments that extended applications for metal pins. Within a few years, Bagshaw employed some 70 workers.

Between the 1840s and 1880s, the United States shifted from importing metal clothing and textile pins to become a leading manufacturing site for their production, use, and even export. Employment in the industry went from a few people working in almshouses to several thousand high- and low-skilled workers in factories in Connecticut and Massachusetts. At the same time, British manufacturers of pins saw a decline from 11 factories in Gloucestershire in 1820 to zero by 1870 and from hundreds of firms in Birmingham to fifty by 1900. However, as new waves of machinery were invented after the Civil War, the United States entered a prolonged recessionary period of declining prices and wages. Some of the deflation in the 1870s through 1900 resulted from macroeconomic policy, but accelerating technology change and disruptions to older systems for apprenticeship and wage premiums for skilled labor also played a causal role.

Textile pins made by the W.H. Bagshaw Company, America’s oldest still-operating pin manufacturer. Courtesy of W.H. Bagshaw Company

Demand for clothing pins leveled off after WWII as ready-to-wear clothing came to dominate the market; yet demand for textile pins has not disappeared. In a sequence also seen in other industries, surviving pin makers in the United States and Europe shifted to more sophisticated production, including specialized combs, precision parts, and needles, including for applications in medicine, aerospace, and electronics. W.H. Bagshaw, now in its 5th generation as a family-owned firm, purchased computer numerical control (CNC) equipment in the early 2000s and continues to employ some 40 people making precision parts from drawn metal. But Bagshaw also still operates the original equipment from the 1870s, and can make up to 1 million textile pins in a day to supply textile firms, primarily in North and South Carolina.

Pins manufactured by computer numerical control machines for use in specialized engine applications and in modular power systems. Courtesy of W.H. Bagshaw Company

We often look to technology history for straightforward stories of disruption, cases in which one technology completely replaces another. Carriage makers did not survive Ford’s mass-marketed automobile. Pin-making machinery, however, tells a more complex story. Inventions from the 1870s are still operating in one factory, even as advanced CNC machines have a 30-year lifetime. Old and new can coexist while supplying different specialized markets. Furthermore, the technology transitions in pin making are interesting in light of present-day concerns that the next wave of artificial intelligence will wipe out employment ranging from trucking to accounting and legal services. More realistically, innovations will help certain markets grow and will generate more employment overall, even as some specializations see jobs shrink or disappear.

Sources:

- Imraan Coovadia, “A Brief History of Pin-Making,” South African Journal of Political Studies 35 (2008), 87-105.

- Peter H. Lindert and Jeffrey G. Williamson, Unequal Gains: American Growth and Inequality since 1700. (Princeton University Press, 2016).

- Steven Lubar, “Culture and Technological Design in the 19th-Century Pin Industry: John Howe and the Howe Manufacturing Company,” Technology and Culture 28 (1987), 253-282.

- Clifford Pratten, “The Manufacture of Pins,” Journal of Economic Literature 18 (March 1980), 93-96.

- Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. (W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1776).

![The reverse side of the John Scott medal, inscribed, “THE SCOTT PREMIUM TO THE MOST DESERVING To John McMullin [sic] of Sinking Valley, Huntingdon County Penna. for a Knitting Machine 1835.”](/sites/default/files/styles/480w_x_330h/public/artifacts-franklin-medal-john-scott-reverse-0011-teaser.jpg?h=2a479378&itok=SfXxEB0j)