America owes its fascination with the yo-yo mainly to Chicago businessman Donald F. Duncan Sr., who spotted it while on a business trip to San Francisco in 1928. It was being used by a Filipino émigré named Pedro Flores, who was beginning to mass produce and sell the simple toy he had known as a boy in the Philippines, the “yo-yo.”

By early 1929, Flores had secured financing, set up his own firm and had turned out more than 100,000 yo-yos, advertising them as the only genuine ones and shrewdly trade marking the name “yo-yo.” Realizing that people had to be shown how to use a yo-yo before they would buy it, Flores hired a team of fellow Filipino yo-yo masters to demonstrate the toy’s amazing tricks. To pump sales, he also sponsored yo-yo contests, awarding prizes at all skill levels.

Flores never claimed to have invented the yo-yo and always pointed out its ancient Philippine lineage. However, he deserves credit for the yo-yo’s first widespread use in the United States, including popularizing the name and initially mass producing and marketing the delightful flying toy.

Because of Flores, a yo-yo craze was sweeping California--just as Donald Duncan arrived on business. An astute marketer, entrepreneur, and manufacturer of, among other things, wooden novelty items and toys, Duncan immediately recognized the yo-yo’s vast potential.

He quickly raised $5,000, purchased initial rights to the yo-yo from Flores and founded Donald F. Duncan, Inc. By October 1932, he had secured Flores’s remaining assets, including the all-important trademark. Until the trademark expired in 1965 and competing plastic yo-yos began to outsell his old-fashioned, lathe-turned wooden ones, Duncan was the country’s leading yo-yo producer.

First Contact

In January 2002, Donald F. Duncan Jr. called David Shayt in NMAH’s Division of Cultural History, asking if the Smithsonian was interested in acquiring materials relating to the Duncan Yo-Yo. A veteran of the family business for most of his life, Duncan Jr. had developed several innovative yo-yos of his own in the 1970s and 1980s. After retiring, he set up a small “Yozeum” dedicated to the yo-yo.

Initiated as a traveling exhibit, the Yozeum became a permanent facility in a leased storefront in Bartlesville, Okla., when Don and his wife, Donna, retired there. Unable to fully maintain the Yozeum, the Duncans were seeking a permanent home for the materials they had so carefully preserved.

Shayt understood that this was a unique opportunity to acquire original documentation and artifacts from the company that was virtually synonymous with 20th century yo-yo manufacture and innovation. Because there were large quantities of paper documentation and photographs, he asked me, an acquisitions archivist in NMAH’s Archives Center, to help evaluate the collection. (The Archives Center serves as a repository for manuscripts, archival collections, and business records, while Shayt’s division cares for three-dimensional objects.)

Realizing the importance of the Duncan collection, we went to Bartlesville to select Yozeum materials for NMAH. The Lemelson Center supported our travel and the costs of shipping the yo-yo items to Washington.

The Yozeum

The Yozeum consisted of some museum-quality display cases, an eight-foot yo-yo, some blown-up photographs on the walls, and a small gift counter. The cases were filled with a dazzling array of yo-yos of every color and type, either dangling by their strings or artfully laid out in colorful patterns. Other displays showed the prizes awarded to Duncan yo-yo contest winners, from patches and trophies to baseball mitts and bicycles, as well as a wide range of related items, including photographs and song sheets.

A workroom curtained off from the public held the business records of the companies founded by both Duncans, along with a wealth of yo-yo ephemera and research materials. Neatly labeled boxes filled several rows of shelves, and two large tables were covered with additional papers spread out in anticipation of the Smithsonian’s visit. After a tour of the exhibit, my colleague joined Don and Donna Duncan in the exhibit space while I tackled the stored materials.

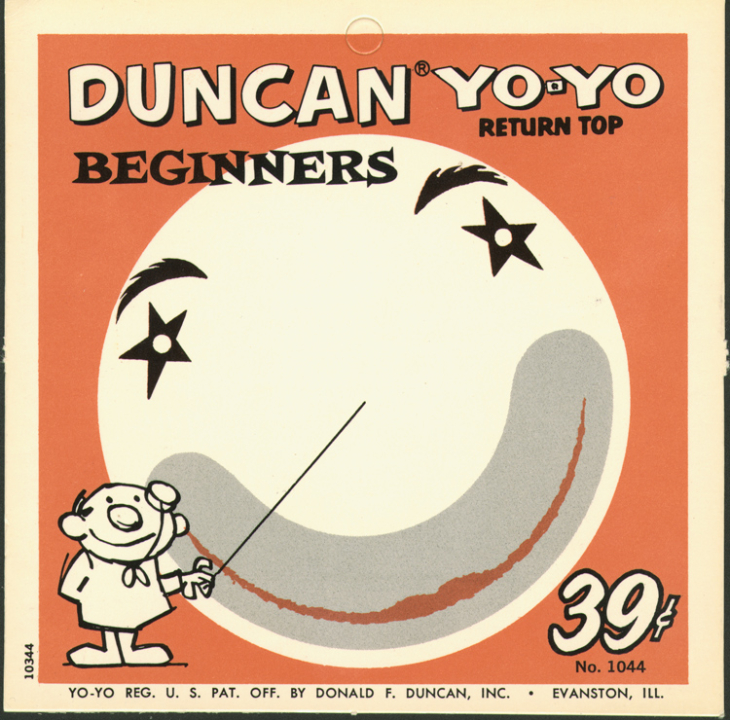

Shayt carefully negotiated and assembled some 50 objects from Duncan and Playmaxx (the junior Duncan’s company), and from other manufacturers, such as Cheerio, Goody, and Royal. Together, these recounted the history of the Duncan businesses and the yo-yo’s wider tale. They included the oldest and newest models; rare and unusual types; those of different styles and price ranges, from “beginner” to “tournament” models; yo-yos of wood, plastic and metal; those with special features, such as flashing lights or whistling noises; and those given away in cereal boxes or other commercial promotions. Not neglected, either, were patches, pins, trophies, and ribbons from Duncan-sponsored contests.

While Shayt took care of the objects, I chose the materials that most thoroughly documented the yo-yo’s history and the Duncans’ involvement. Primarily, these were from the 1930 Donald F. Duncan company, including incorporation papers; legal, advertising, and sales records; and manufacturing documentation such as a film of the company’s Luck, Wisc., production line in action.

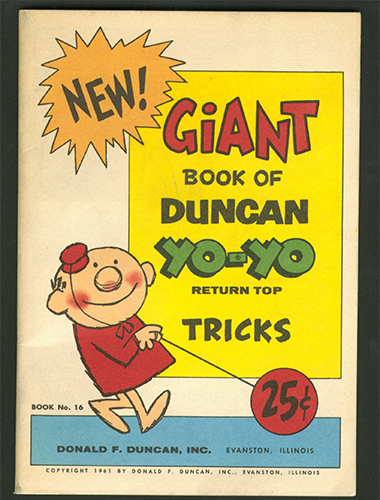

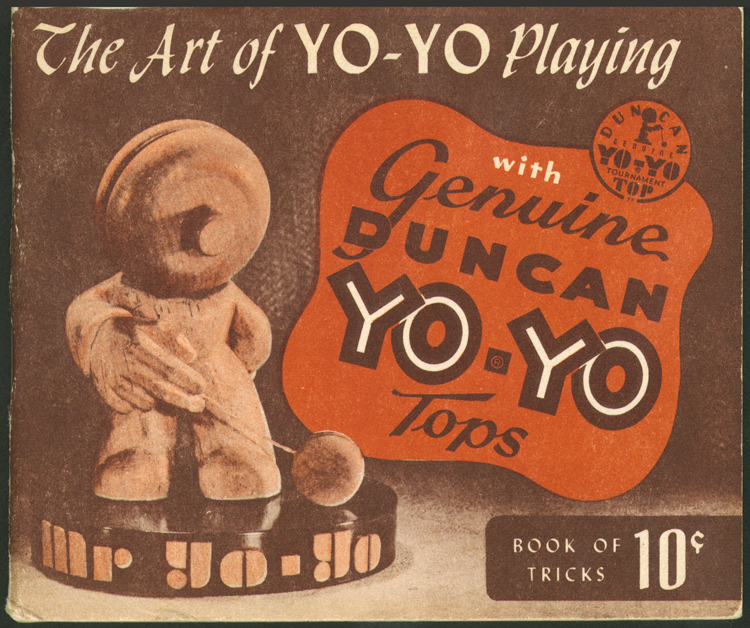

The company’s marketing efforts are documented by contest rule books, illustrated books of yo-yo tricks, photos of yo-yo contestants and their prizes, guidelines and rules of conduct for demonstrators, and the field manuals used to lay the groundwork for Duncan-sponsored events.

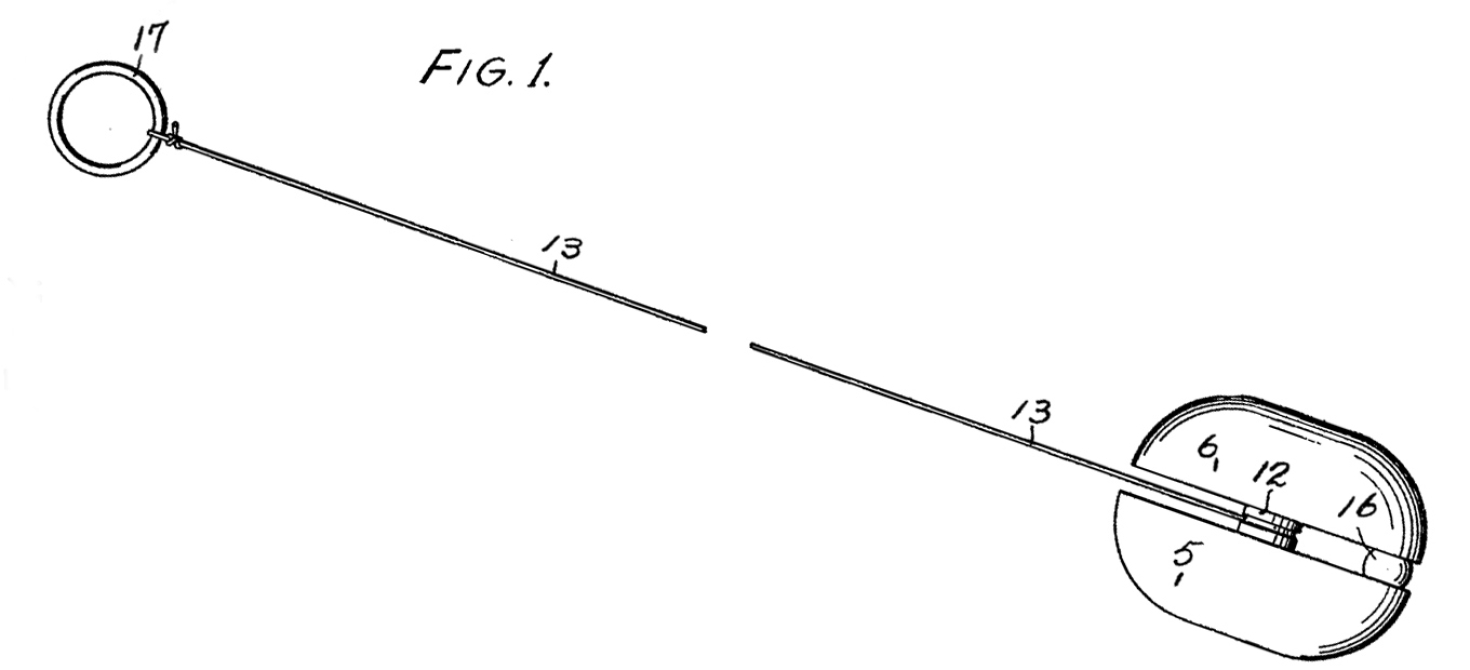

Of additional interest were the records from 1972 to 1994 covering Playmaxx, the company founded by Don Duncan Jr. to produce a more technologically advanced plastic yo-yo. These consisted of market research, confidential business plans, marketing strategies, production and operating data, sales records, and advertising. The best included a patent record book, a set of original patent drawings, and design sketches—even the archetypical sketch on a dinner napkin!

Other finds, especially news clippings and published articles, chronicled the yo-yo’s broad sweep, from its origins in the Philippines to its introduction to 18th century Europe and on to Pedro Flores. Duncan competitors are also represented in the archives by advertisements, catalogs, and sales materials.

The yo-yo’s renewed popularity in the 1980s and 1990s is caught in videotapes of yo-yo competitions, books of yo-yo tricks, reference guides to yo-yo collecting, and information on Tommy Smothers, whose Yo-Yo Man character was instrumental in the comeback of this ancient Filipino toy.

In all, I selected some 14 cubic feet of archival material, out of a total of about 25 cubic feet. Throughout our day of Yozeum evaluation and selection, Shayt and I kept in close touch on what we were finding and choosing for the Smithsonian, in order to strengthen our respective components of the collection. With the final object carefully wrapped, the last papers securely boxed up, and the deed of gift signed by Donald Duncan Jr., another collecting trip concluded successfully; the Smithsonian now held the nation’s most comprehensive collection of objects and archival materials on the history of the yo-yo.